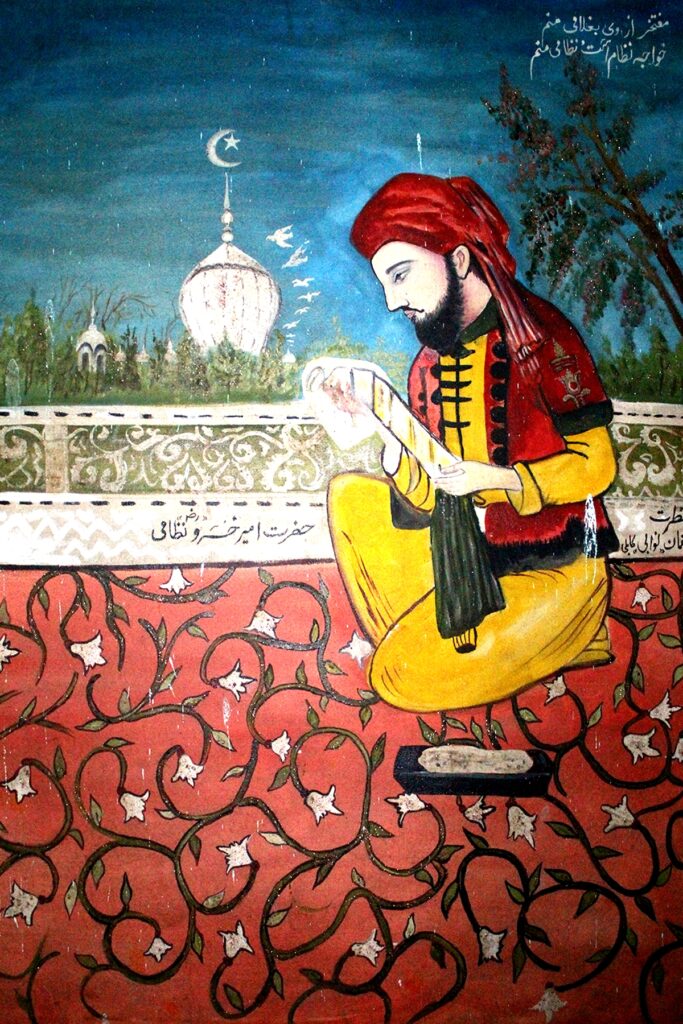

Nizamuddin Auliya to Amir Khusro: I am weary of everyone, even myself, but never of you

Amir Khusro would pray most of the night. Once his master Nizamuddin Auliya asked him: “Turk, what is the state of being occupied?” “There are times at the end of the night when one is overcome by weeping,” he replied. “Praise be to God, bit by bit is being manifest,” Nizamuddin said.

But what was being manifested in Khusro?

Amir Khurd, the author of Siyar-ul-Auliya, which details Nizamuddin’s life, says Khusro met Nizamuddin when he was living at his maternal grandfather, Imad-ul-Mulk’s house. The young Khusro would present each of his poems to Nizamuddin. One day, Nizamuddin told him to compose poems in the style of Ishfanis — love poetry.

Khusro was a courtier, a poet. He went to battle with his sultans; he saw thousands being massacred. This was not Nizamuddin’s world. It was the anathema, the antithesis. Nizamuddin, like all Chishtis, had nothing to do with king and court. He would not let sultans enter his home let alone seek fame in their courts. Sultan Jalaluddin wanted to visit Nizamuddin’s khanqah. The master said: “My house has two doors. If the sultan enters through one, I will exit through the other.”

Nizamuddin spent his life providing happiness to the human heart and helping the poor — for by doing so he realised his Maker.

You would ask what brought a court poet to the khanqah of a Sufi ascetic who had given up the world to serve the poor? This was a Sufi who had nothing of kings. He could not care less for what they stood for. He had no time for them. Nizamuddin had one King.

Destiny brought master and disciple together. Nizamuddin was born in Badaun in 1244. A little away in Patiali, around 1253, Saifuddin Shamsi, a Turk, celebrated the birth of his second son. The Mongols had driven thousands out of Central Asia. Saifuddin joined the army of the sultans of Delhi. He married, Daulat Naz, the daughter of Imad-ul-Mulk, the army minister of the sultan. Imad-ul-Mulk was a strong man and kept a hawk eye on the recruitment and salaries of the army leading to a disciplined and efficient fighting force.

Abul Hassan Yameen Al Deen was born to Saifuddin and Daulat Naz. He was born into riches and a milieu where brother killed brother and nephew his uncle to sit on the throne. The sultan’s court was a cauldron of intrigue, deceit, and murder. Abul Hassan’s father, Saifuddin, was the sultan’s soldier, his grandfather, Imad-ul-Mulk, a key member of the royal court, the epicentre of political deception. Abul Hassan was cradled in this air of evil design, distrust and conspiracy.

Saifuddin lived adjacent to a man with a gift for prophecy. He took one look at baby Abul Hassan and said: “You have brought someone who will be two steps ahead of the poet Khaqani.”

Abul Hassan would grow up to be known as Amir Khusro — the master poet and musician; the confidante of sultans; and oddly enough the favourite disciple of Nizamuddin — the dervish who despised politics, who shunned sultans.

Saifuddin died in battle when Abul Hassan was very young. Imad-ul-Mulk brought up the boy. Abul Hassan lived in this world — where the power of the sword thrived with the power of money. Unlike Nizamuddin, he never went hungry as a boy. Poverty was alien to him. He was precocious. His tongue was swift; his pen even quicker. The boy’s magic with word play won him the pen name Amir Khusro. The sword was of no interest and neither was money. Khusro was lost in the art of words. He lived by them. And he could put music to words too. He was a master of verse and song.

Like his father and grandfather, Khusro joined the courts of the sultans but not as a soldier – he was their poet. The sultans and noblemen were whimsical in their politics and in their patronage of the arts.

Amir Khusro once wrote:

“Composing panegyric kills the heart,

Even if the poetry is fresh and eloquent.

A lamp is extinguished by a breath,

Even if it is the breath of Jesus.”

Khusro did what he had to do: as court poet, he had to sing the praises of his political master. But he would first emphasise that he cannot walk the path of life without Nizamuddin Auliya, his spiritual master, as precious to him as his own life.

When Jalaluddin Khilji was slaughtered by his nephew, Alauddin Khilji, and his head was strung up on a spear, Delhi was numb. Amir Khusro put matters into perspective: “And while we shed our tears for the old sultan, who was so cruelly killed by his loved one, we must remember that Jalaluddin had slaughtered his master to seize the throne.”

As sultan Alauddin Khilji passed, some say poisoned by his general Malik Kafur, Khusro wrote: “Why conquer so many realms and cities when you cannot get more than four yards of land after your death.”

Yet Khusro described his true master, Nizamuddin Auliya, as this: “He is an Emperor without throne and without crown. But the rulers stand in need of the dust under his foot.”

“What do you desire?” Nizamuddin once asked Khusro. “The sweetness of verse,” he replied. “Go and bring that bowl of sugar from under the cot. Eat some and sprinkle the rest over your head,” Nizamuddin said.

From that day, Amir Khurd writes in Siyar-ul-Auliya, Khusro’s words found the sweetness he was looking for and like the Sun, his fame captured east and west. Khusro had also captured Nizamuddin’s heart.

“Repeat my prayer, for your permanence is dependent on my permanence. They should bury you next to me,” Nizamuddin would often tell Khusro.

When his master would retire for the night, no one would be allowed to enter his chamber, only Khusro could. “What news Turk?” Nizamuddin would ask. And the poet would tell his master what had transpired in the treacherous court and the kingdom that day. When Khusro would leave, Nizamuddin would close the door. A candle would be seen burning in his room. Nizamuddin was immersed in prayer. He would recite this couplet: “Come sometimes and have a glimpse of me and the candle. When breath leaves me, the flame goes out of the candle.”

He remained like that for most of the night. Nizamuddin would emerge in the morning with an ecstatic glow around him. His eyes would be red. Khusro would ask in whose embrace had Nizamuddin spent the night because his eyes were so red, yet his face was radiant. But even Amir Khusro, the courtier, who played sultans like a violin, could not sit in the same room as Nizamuddin for too long. He would tremble and run out of the room ever so often. When one of Nizamuddin’s devoted disciples, Burhanuddin Garib, asked Khusro why he was running out of the room constantly, he replied: “When a mirror is placed before a Sun, how can one see his face in it?”

Khusro had access to Nizamuddin like nobody ever had. Burhanuddin Garib was devoted to Nizamuddin. He would look after the kitchen, overseeing the preparation of food. He was 70 and would lean on a blanket. Ali Zambeli and Malik Nusrat, attendants of Sultan Alauddin Khilji and disciples of Nizamuddin, told the Shaikh that Burhanuddin Garib was being arrogant as he now needed to sit on a blanket.

Nizamuddin was troubled. No one should display any sign of arrogance. Burhanuddin Garib came to speak to Nizamuddin, but he did not utter a word. Nizamuddin’s attendant, Iqbal, told Burhanuddin Garib that he should leave the khanqah that very moment. These were his master’s orders. The man, whose devotion to his master had never been questioned, was shocked. He had no words, and left the khanqah to stay with a friend, Ibrahim Tashtdar. He was grieving, but Tashtdar did not care. Burhanuddin had hurt Nizamuddin. He could not stay in his house. No one would keep him.

Burhanuddin came back to his house possessed by a sadness that could only be cured if Nizamuddin pardoned him. What wrong he had committed he did not know. Burhanuddin had never dreamt of being arrogant erektil dysfunktion läkemedel. He was always lost in prayer and in remembrance of his Maker.

Khusro took up his cause. Nizamuddin did not budge. The courtier knew his master would melt. He wrapped his turban around his neck and presented himself before his master like criminals did when they surrendered. Nizamuddin was surprised. What was Khusro up to? He asked him to forgive Burhanuddin Garib. Nizamuddin gave in. Khusro brought Burhanuddin Garib to the master with his turban around his neck.

The bond of destiny

Nizamuddin suffered from extreme depression when his young nephew, his sister, Zainab’s son, passed away. He became withdrawn; he would not speak. His disciples were worried. They had never seen their master this way. Khusro did not have the magic up his sleeve to cure the depression until one day he saw a group of women, dressed in yellow, dancing and singing their way to a temple. He stopped them and asked what they were doing. Celebrating Basant, they replied. The courtier dressed up like a woman in yellow and went dancing and singing to his master. Nizamuddin smiled. Every year, Basant is celebrated at Nizamuddin’s shrine to mark the day Khusro got the master’s smile back from the depths of grief and depression.

If the sultan Jalaluddin Khilji pampered Khusro, Nizamuddin cradled him like a child, never letting go of his hand. Nizamuddin fondly called Khusro TurkAllah, the Turk of God. “I am weary of everyone, but I am never weary of you. I get weary of everyone, even weary of myself, but I am never weary of you,” the master would say. The slave, God Almighty willing, would be next to the master even in Paradise.

Once in a dream, Nizamuddin saw at the end of Manda bridge, near the gate in front of the house where Najeebuddin Mutawakil, Baba Farid’s brother, stayed, water flowing, serene and pure. Mutawakil was sitting on a high place. It was an exhilarating experience, he would recall. Nizamuddin thought of asking God to bless Khusro. The master knew his prayer would be answered.

Khusro was always disciplined. Even in the height of his love affair with the court and its material wonders, the poet made sure he made time every day to polish his craft — words and verses that he put to rhythm and tune. And perhaps, he wrote this verse after being overcome with the sense of the Divine one night.

I do not know what abode it was, that place where I was last night.

On every side I saw the dance of the Bismil in that place I was last night.

I saw one with the form of an angel, the height of a cypress, cheeks like tulips.

From head to toe, I quivered, my heart astir, in that place where I was last night.

Rivals, listen to that voice, the voice which calms my raging fright.

The words he spoke left me in awe, in that place where I was last night.

Mohammad was the candle illuminating the assembly,

O Khusro, in that place which is no place,

And God himself was the head of that gathering,

In that place where I was last night.

The elixir of Divine Love that Nizamuddin conjured up within Khusro was an addictive potion. That was being manifest. Worldly pleasures were no match for that realm — the sanctuary of peace and love; of a soul immersed in the flood of Divine joy. Khusro would drown in that love.

Amir Khusro would join his master on the banks of the river Jamuna. Master and his favourite disciple would sit for hours, sometimes discussing the politics of the time, but mostly they would travel to another world; the world of humanity and tolerance where they would find their Maker.

One morning, they were by the banks of the river when people were bathing and worshipping. Nizamuddin turned to Khusro and said: “Everyone has a faith, a qibla (direction of the Ka’aba in Mecca) which they turn to.” Khusro replied: “My qibla is where your cap is.”

And it was perhaps after watching people worship by the Jamuna that Khusro uttered these words:

“Oh, you who sneer at the idolatry of the Hindu, learn also from him how worship is done.”

Tolerance ran through the veins of his master and entered Khusro’s pores.

Nizamuddin served the poor for decades. His health had begun to fade. Khusro was away with the Sultan Ghiyasuddin on a campaign in Bengal when he felt a sense of unease. It was a matter of time that the master would be reunited with his Love. Amir Khusro was journeying back from Bengal. The master went home. It was 1325.

Khusro came back to Delhi. He went straight to that garden where his master lay and uttered these words:

“The fair one lies on the couch with her black tresses on her face.

O Khusro, go home now, for there is only darkness in this world.”

There was nothing left for Khusro. No reason to live in this world. Who would give him comfort after he returned from the barbaric court of the sultan? Who would fire his soul worn down by the vulgarities of the nobles? Who would revive the joy after the doldrums of the court, the doldrums brought on by sycophantic verses he would have to churn out day after day until they deadened his mind? Who was there to read the words he wrote, to listen to the song of his heart?

Khusro once said: “The Khwaja is not made of water and clay. The lives of Khizr and Jesus have been mixed to form his being. Wherever his breath reached, mountains of grief gave way.’

There was no breath to cure this grief. Instead, it seemed the mountains of grief could — and would —take life away.

The soul that shielded Amir Khusro against the raging storms was in the other world. He had to go there.

After six months of grieving, Amir Khusro surrendered himself to his master. The soul could not survive the darkness of this world on its own.

He lies a few feet from his master. Together in this world, they are together in another.

Guest Authors

- Aatif Kazmi

- Absar Balkhi

- Afzal Muhammad Farooqui Safvi

- Ahmad Raza Ashrafi

- Ahmer Raza

- Akhlaque Ahan

- Arun Prakash Ray

- Balram Shukla

- Dr. Kabeeruddin Khan Warsi

- Faiz Ali Shah

- Farhat Ehsas

- Iltefat Amjadi

- Jabir Khan Warsi

- Junaid Ahmad Noor

- Kaleem Athar

- Khursheed Alam

- Mazhar Farid

- Meher Murshed

- Mustaquim Pervez

- Qurban Ali

- Raiyan Abulolai

- Rekha Pande

- Saabir Raza Rahbar Misbahi

- Shamim Tariq

- Sharid Ansari

- Shashi Tandon

- Sufinama Archive

- Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

- Syed Moin Alvi

- Syed Rizwanullah Wahidi

- Syed Shah Shamimuddin Ahmad Munemi

- Syed Shah Tariq Enayatullah Firdausi

- Umair Husami

- Yusuf Shahab

- Zafarullah Ansari

- Zunnoorain Alavi