Sufi practices as the cause of spiritual, mental and physical healing at Chishti shrines in India and Pakistan

Dargahs is a Persian word and it literally means “court”, a mausoleum of a Sufi (Chaudhry, 2013). The English word shrine accurately conveys the meaning of Dargah. Dargahs are primary parts of the rural and urban setting of Pakistan. Sufism being a religious, political, mystical, communal and cultural entity has influenced the structure of the social order of the subcontinent in general. Some primary documents on Sufism can help understanding of the topic such as Al-Hujwīrī (1911/1976), Aulia (1985), Dehlavī (1990/1992) and Khurd (1885). For a detailed note on the evolutionary process of Sufi orders and on the origin and development of Sufism in the Islamic world with particular focus on Indo-Pak subcontinent, there are some fine pieces of secondary resources which can be useful for the subject matter, such as Anjum (2011), Chaghatai (2006), Haeri (2000), Islam (2002), Khanam (2009), Nizami (2007) and Schimmel (2003).

Dargahs are the meeting places of the Sufi brotherhood and have emerged as socioreligious institutes. The development and the spirit of “popular Islam” (shrine/Dargahbased Islam or visiting Dargahs) have been established with the passage of time (Hassan, 1987). “Popular Islam” has a noteworthy character to collaborate with the mystical requirements of societies connected to it. Dargahs’ admirers visit them in order to address their communal and mental complications. On their visit, they execute many ceremonies assisted by definite dogmas (Khan & Sajid, 2011). Thus, Dargahs have given rise to several rituals which show the fundamental features of the cultural legacy of the communities.

Followers of Dargahs and their conception and interpretation of Islam are organised by their established traditional performances, which have grown within generations and strongly remain there to perform an essential role to shape their lives and activities.

This is supported as,

It seems that in order to cope with the conditions of their daily lives within their social and cultural contexts, these Muslims do not hesitate to resort to traditions outside strict religious parameters. Such attitudes are translated into devotional practices shared among people of diverse religious back-grounds who, in order to deal with the problems of health, economy, or to gain fertility, resort to rituals of vow in shrines belonging to any tradition. (Rehman, 2006, p. 23)

It is important to initially define what a practice or ritual is. The presentation of traditional performances arranged by belief or by spiritual outcome is called a ritual. Ritual is a precise, visible way of behaviour demonstrated by all recognised social orders. It is therefore conceivable to cite ritual as a manner of describing human beings (Penner, 2017). Ritual is the base of the human shared contract that allows the general mutual interactions that make human life prospective (Khan & Sajid, 2011). In a more elaborated manner, we can say that the term ritual refers to a repetitive social practice consisting of a series of symbolic activities which are governed by a set of ideas often encoded in a myth. Songs, dances, gestures, speeches or the manipulation of objects are a few examples of such social practices. As described by Shultz and Lavenda (2009) in the book, A Perspective on the Human Condition, a ritual must follow four conventions. These four conventions are:

It must be a repetitive social practice.

It must not be a part of daily life routines.

It must be governed by some sort of ritual plan.

It must be encoded in myth.

We can say that ritual is an observance involving a number of activities that are achieved in a given order. Rituals assist people and cultures to give them a sense of belonging and intimacy. Ritual performance and faith can be taken as methods of figurative announcement concerning the societal pattern. It is an explicit and visible behaviour shown by all established societies. Thus, viewing ritual as a way of describing or defining humans is a definite possibility (David, 2007). Different kinds of rituals are an essential part of all known human societies that have existed to date.

It is pertinent to explain what is meant by the performance of a ritual. The performance of a ritual produces a dramatic like structure around the actions, symbols and occasions that form a performer’s experience and rational organisation of the world, making the chaos of life simple, moreover ritual performance also is an execution of wisdom based structure which is quite clear in its composition (Bell, 1997). This experience is described as “not only is seeing believing, doing is believing” (Myerhoff, 1997, p. 223). Mutually shared rituals facilitate the expression and confirmation of collective beliefs, patterns and ethics and are consequently indispensable for upholding communal constancy and group synchronization. Ritual state of execution is basically vibrant in its nature and in its action which puts emphasis on the unification of the group by reducing individual differences (Sosis & Alcorta, 2003).

Punjab (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2017) was among the first provinces of South Asia to come across the significant influence of early Sufi mystics. The role of Sufi rituals and their significance in Punjab’s socio-religious set-up has been substantial. Sufi rituals are those rituals which are practised at Sufi Dargahs and which have been evolved through generations and play a significant role in the lives of general public. Pilgrims and followers come to visit the Dargahs in huge numbers on a regular basis, either individually or in groups, to express their love and respect to the Sufi. It appears that these Muslim Sufi followers are not reluctant to practise traditions contradictory to stringent religious norms and standards in order to handle hardships of daily lives which they have to face in their social and cultural circumstances. Such beliefs are transferred into ceremonial practices observed by people of miscellaneous religious backgrounds who, in the quest to cope with economical and health difficulties or to be wealthy, turn to rituals in Dargahs regardless of any tradition (Raj & Harman, 2006).

An important aspect to note is that spiritual transformation within human beings can be seen or examined once they are achieved, but the process through which these transformations occur cannot be analysed by any means. It is said that, “belief system as part of social structures has its own sociological implications. Belief system is part of subjective culture that is usually imparted in human consciousness through mass media, cultural artifacts and educational institutions” (Farooq & Kayani, 2012, p. 336).

Devotional beliefs performed at the Dargahs of South Asia these days have an origin in Islamic history going back to the reverence of Prophet Muhammad PBUH who is considered as an intercessor between Allah and his followers (Lwise, 1985; Schimmel, 1982, 1985). The principles of these multiple institutions in Sufism are intensely related to ancient Islamic legacy and the same spirit is shared by diverse practices and rituals of different styles. The distinction among different kinds of Dargahs’ devotees is based on their spiritual standing instead of their socio-economic positions in the community. In the world of living Sufism, a devotee who serves a Sufi or works at a Dargah will be respected more than others (Frembgen, 2004). Study of Dargahs is difficult because their impacts are not immediately recognisable. The perspective of Dargah devotees vary geographically depending upon the social order of that particular region (Campbell, 1998). For example, people living in the Punjab are more inclined towards Sufism. Their commitment towards Dargahs is thus more intense. They prefer visiting Dargahs for treatment of illnesses or infertility instead of going to doctors or to hospitals (Frembgen, 2004). Also, many people visit Dargahs to seek a solution to their economic problems (Kurin, 1983). For some people, visiting Dargahs is also a matter of belief and a family tradition to fulfil aspirations of Sufism. In fact, practising Sufism has become a power which displays that Islamic spiritual resources are well equipped to address different concerns of the modern world (Farooq & Kayani, 2012).

…some groups combined the idea of the shaikh as exemplar of “correct” Islam with rural, shrine-centered beliefs and practices, emphasizing the meditational, intercessory aspects of his role over the directing aspects. This was particularly true for the Ahl-e Sunnat and the Chishti order as well as many of the other Sufi tariqas. (Pemberton, 2002, p. 73)

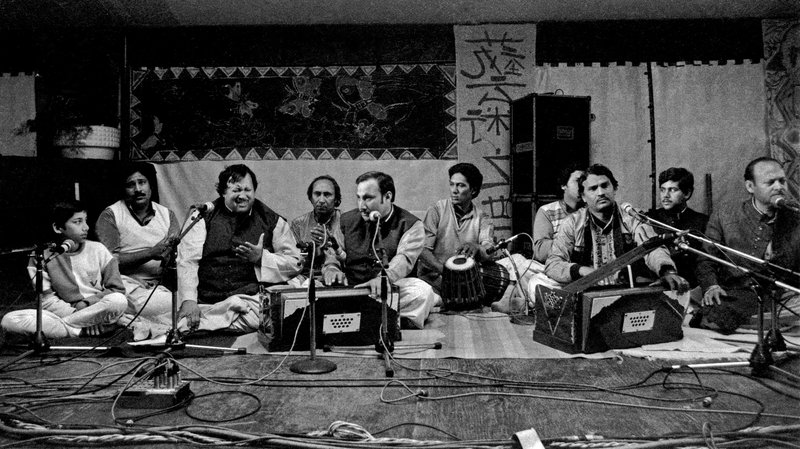

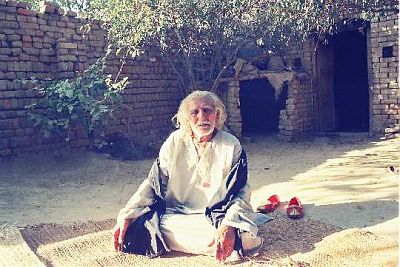

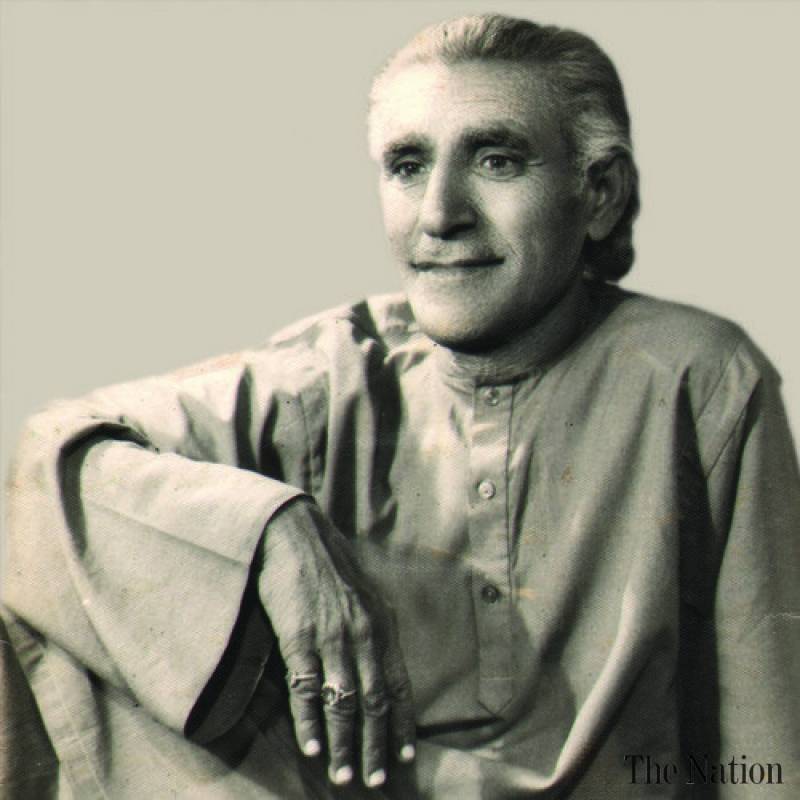

The following section anthropologically examines the performance of rituals incorporated with the institution of Dargahs. After the Wisal (physical demise) of the Sufi, the place where he is buried is named as Dargah. Due to spirituality, love and respect for the Sufi, the Dargah becomes a divine place for pilgrims to visit. A large number of followers strongly believe that Sufis remain spiritually alive even after their Wisal and are blessed by Allah with the powers to listen and serve as an intermediary between Allah and them. According to their popular beliefs, Sufis understand the problems of the devotees even better than themselves and hence can communicate their prayers in a more effective manner to Allah. Thus, chances of acceptance of their prayers are increased. In pursuit of their beliefs, the devotees of Sufi Dargahs practise certain rituals. Music is an important element of the Sufi Dargahs, where music artists sing spiritual rhymes. It is the way of earning as well because those who are visiting the Dargah often donate some amount. Sufi poetry and music are imperative sources of emotive expression for the aficionados. Folk poetry and music practices are very popular and much valued, nourished and adored by the people. For some Sufi poetry and singing is the main form of insightful amusement in the spontaneous congregations in the village area. Dhuras, Kafis, Vars and Mayas (Punjabi poetic expressions) are some of the widespread types ingrained in the village culture. Sufiyana Kalam (Sufi Poetry) is a usual feature at the Dargahs all over South Punjab and most have a team of musicians frequently using a harmonium and Dhol (drum) (Vandal, 2011). In contemporary times, the Sufi philosophies can be realised merged in the prevalent pop music of Pakistan. Popular bands such as Junoon, the world celebrated semi-classical musicians and singers such as Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (late), Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Perveen and Pathan-e-Khan have intermingled Sufi music with the modern pattern (The Role of Music and Dance in Sufistic Ritual Practice; Sanat, 2017).

The function of music, poetry and dance touch to its height on Urs commemorations. Urs is an Arabic word and commonly used in Sufi literature which denotes marriage between bride and bridegroom. The demise of a Sufi is considered as a time of reunification with his creator, hence observed as a happy event. Urs is also the mutual name for various Sufi rituals at the death centennial of a Sufi. Each Sufi order observes its individual Urs performances. Frembgen (2004) describes this as follows, for the Wali (friend of Allah) physical demise results in access into the “real” life embodied in the mystical union (maqam al-wisal) with Allah, a moment of unification which is ritually celebrated as a “holy marriage”, an Urs, with Allah (Juergen, 1998). Therefore, Dargahs are denoted as the places where the Sufi rests safe in perpetual unity with his Beloved.

The celebration rituals at the Urs and its related carnival (Mela) are a yearly occasion very much expected by the communities for these areas. Though musical activities are condemned by the orthodox Muslims, on the occasion of the Urs the followers, both men and women, openly express their mystical states through Sufi music and dance. They have faith that visiting, praying and practising rituals will enable them to attain a better socio-economic position, strong ethical character, perfect health, spiritual contentment and mental satisfaction. Thus, the function of a Sufi Dargah is versatile and covers different dimensions of life, i.e., it guides people economically, socially, politically and culturally in daily life. Its contribution in solving people’s problems has always been, and will remain of prime importance (Malik, 1990). Levin (2008) also agreed with this perception that devotees visit Sufi Dargahs in order to accomplish their economic, social, psychological and spiritual goals.

It has been a common practice all over the world to visit holy places in order to acquire religious satisfaction, seek forgiveness of sins and fulfilment of desires. Journey to holy places, such as Dargahs and tombs, has always been considered as an honourable activity and people feel that their bodies and mind are purified by spending time at Dargahs. With the passage of time, Sufi Dargahs have incorporated the aspiration of the native people along with regional cultural activities and customs as part of the different religious rituals at Sufi Dargahs (Abbas, Qureshi, Safdar, & Zakar, 2013). Purposes of Dargahs consist of social sharing, provision of amusement in the shape of devotional music and songs (Qwwali), making people more humane, sharing of food, sweets, cash, etc. (Kurin, 1983). Qwwali is a mystic chorus or melody. “Through the rhythms of Qwwali the listener may be opened to inrushes (warid) of knowledge and awareness through which he reaches ecstasy (wajd). If he ‘finds’ Allah within this ecstasy then he has experienced the true Sama” (Armstrong, 2001, pp. 209–210).

Being a social institution, Dargah with its multipurpose role, executes definite purposes for the public attached to it. The majority of the regular visitors at Sufi Dargahs at Urs day include deprived and marginalised sections of the society such as Khusraay (transvestites), singers, prostitutes, traditional healers and fortune-tellers. The presence of such people at Dargahs in the Punjab is common. Sufi Dargahs provide these underprivileged classes of society with self-confidence by offering them some kind of peace in their lives. It is vital to mention that most of the visitors to Sufi Dargahs belong to poor socio-economic and illiterate backgrounds living stressful lives. The few privileged/rich followers who visit distribute money, gifts and meal which is known as Langar among the people present at the Dargahs and this aspect is a source of attraction for the poor local people to visit Dargahs. Langar means free public kitchen aimed at sharing food with others irrespective of religion, class, cast, colour, doctrine, age, gender or social rank. This kitchen is opened for all and meant to make food available to all devotees and visitors. Devotees fervently donate to the Langar either by contributing food items or by partaking in the cooking and deliverance of the food. Thus, the concept of Langar is to maintain the norm of impartiality among all people of the society. Moreover, the ritual of Langar articulates the morals of community-sharing, comprehensiveness and unanimity of all human races. Distribution of Langar is a surviving Chishti tradition which is still practised with the same fervor at all the Chishti Sufis’ Dargahs of India and Pakistan.

Sufi Dargahs not only attract religious people for the performance of their spiritual rituals but also attract secular tourists and others for social mixing, fun and recreation (Abbas et al., 2013). Dargahs usually make mystical ease available in the social-cultural set-up. The ultimate quest of man is the complete attainment of happiness and inward satisfaction instead of getting simple temporary relief. People mostly approach Dargahs to get mental satisfaction and the majority are successful in fulfilling this objective.

Method

The following multiple functions of Dargah in terms of visitation to it elaborates how local culture and belief system collectively exists in a rural community, in particular, Punjab. For this purpose, an anthropological study (questionnaire/survey) was conducted to find out the result and for that two important Chishti Dargahs of the region were selected: Baba Farid Ganj Shakar and Khawaja Shams ud Din Sialvi. Both Dargahs are highly venerated and visited by the region’s community.

A qualitative research approach and anthropological analysis for the production and study of the data is used which consists of a description and recollection of the chronicles, discussions with different connected personalities together with Dargah visitors and managers, personal examinations of the execution of rituals, empirical investigations and concepts which have facilitated in constructing a valuable investigation of the specific selected subject matter. An empirical examination is carried out for the case study of both Chishti Dargahs in that several primary and secondary sources are applied for data collecting.

Sample

In total, 15 out of 19 respondents were homeless and jobless and they permanently lived on the Dargah premises.

Interview Schedule

The following are questions which were designed to evaluate the topic. The questions were put to different visitors at Chishti Dargahs. Questions also helped in getting necessary information while conducting personal observation:

– Which class or groups of the society mostly pay visit to the shrine/s?

-Why do people come to the shrine/s?

-What specific purpose/s people visit the shrines for?

– Do people feel that all their desires fulfill after visiting the shrine/s?

– What do people feel when they visit the shrine/s?

-What kind of “rituals” do people perform at the shrine/s?

– What are the main objectives behind those “rituals”?

-What is the spiritual link or spiritual relationship between the visitors and the Sufi?

-What are the benefits visitors get from the shrine or from the Sufi?

– What is the nature of those benefits; spiritual or materialistic?

– Is there any spiritual, mental or physical healing visitors get at the shrine/s or they just pay a visit in order to fulfill their worldly objectives?

-How both shrines are serving in satisfying the socio-religious requirements of the local community in specific and overall of the Sufism’s followers?

-Do performed practices at the shrine/s are purely religious requirement or visitors merely perform them according to their own native cultural environment?

-Urs is a shorter but perhaps more dramatic version of the yearlong activities at the shrine/s. So how far the Urs is a microcosm of the larger Punjabi society?

Data-gathering techniques

For getting data from both primary and secondary sources the study comprises of multiple data-collecting methods at the two locations that can be categorized into two types: interviews and personal observations. Semi-structured and in depth interviews One of the main resources for the qualitative research is operating different interviews. Interviews of both individuals on a one-to-one basis, telephone interviews and group interviews have been conducted. Prior to all interviews the questions were planned and finalized emphasizing on the topics but a space for open ended and informal dialogues was also left because the spiritual understanding of every single person is different and cannot be limited to one short answer. For the most part, interviews were more open ended and less controlled.

Telephone conversations were recorded at both Chishti Sufi Shrines in order to collect relevant data.

Personal observations

With the purpose of discussing and elaborating the Sufi practices at both Chishti Dargahs personal observations of the practices were undertaken. The movements and communication of people in the open public spaces (in and around the Dargah) were observed carefully. Field notes and videos and photographs were taken for the period of observations.

Results

The major objective of paying visits to their Dargahs is the fulfilment of the desires based upon social, financial, political, religious, physical, mental and mystical aspects of the visitors’ life.

Fulfilment of social desires

The key reason for visiting Sufi Dargah is to pray to Allah for fulfilment of wishes such as marriage of daughters within respectable families, success in exams, achieving love marriages, favourable solution of family disputes and conflicts, better future of children and child birth. When asked, respondents said that they visited a Sufi Dargah to pray for their children’s success in exams. They believed that praying for children would help them pass and secure good marks in exams. They have a firm belief that prayers offered/asked at Dargahs have much more chances of acceptance by almighty Allah as Dargahs are holy places (Abbas et al., 2013). Dua Mangna (praying to Allah), one of the major practices at any Dargah, provides the probabilities of gratification to the visitors by offering them a space to accommodate their daily difficulties (Khan & Sajid, 2011). Some drug addicts and other underprivileged people could also be seen at the Dargah.

Fulfilment of financial desires

Mostly people denied any financial gain as their reason to visit Dargah. There were not many who said that they visit for economic prosperity and interestingly they shared common reasons: unemployment, lack of professional growth, low business, etc. They were quite confident that praying at the Dargah would bring good fate to them. A small number of devotees shared their success stories of praying for financial benefits. According to them, they had witnessed an improvement in their business and financial status due to the blessing of the miraculous Sufi. Similarly, few believed that spiritual power of the Sufi of Dargah had facilitated their monetary prosperity, social prestige and internal satisfaction (Abbas et al., 2013).

Fulfilment of physical serenity

People visit Sufi Dargahs for medical purposes as well. They believe that they would throw out their diseases free of cost by praying at a Dargah, and by eating the holy Tabbarak (blessed food) including Langar, sugar or salt. According to these people, even chronic and fatal diseases, such as hepatitis, tuberculosis and typhoid, get cured completely by eating holy salt and sugar and by drinking Dam Wala Pani (sacred verses recited on water) available at Dargahs. In addition to that, sacred oil is also available. People apply this holy oil to their heads in order to enhance the shine and health of hair and sharpen their memories, and applying on body joints to increase their strength. Another interesting observation is that water bottles are placed near the Sufi grave so that the people offering Fateha (special sacred prayer) may blow verses on the water to make it dam wala pani (blessed water). This holy water is drunk by the people who are there to seek a cure from all kinds of diseases. Contrarily, only a few respondents, that is, three out of 19 denied any sacredness associated with items placed at Sufi Dargah. In their opinion, these items only exhibit culture and tradition of Sufi Dargahs (Devotees, personal communication, September and December 2014).

Fulfilment of the mystical desires

Mental peace and pleasure are the main attractions which brings people to Dargahs. People shared that they like to spend time at Sufi Dargahs whenever they get psychologically, emotionally and mentally disturbed. The time spent at Dargahs works as meditation and grants them peace of mind and positive energy for success and enables them to move forward confidently in pursuit of their wishes. Participants said that they get purified by prostrating to Allah and by requesting forgiveness for their sins. Dargahs provide them with the chance to talk to Allah. Their pleas in front of Allah help them to do Tazkia-e-Nafs (self-purification). They leave Dargahs satisfied and edified (Abbas et al., 2013). This is an undeniable fact that the main reason for visiting Sufi Dargahs by common people is to cope with their social and psychological problems (Levin, 2008).

In Pakistan, the pressure and strain of contemporary life is directly linked with the social hitches, lack of resources and lesser education (Husain, Chaudhry, Afridi, Tomenson, & Creed, 2007). Dargahs’ devotees look towards Sufis as mediators to overcome possible challenges by meditation and therapeutic rituals (Fleiderer, 1988; Glik, 1988; Pirani, Papadopoulos, Foster, & Leavey, 2008). Fulfilment of divine needs is fundamental to the working of Sufi Dargahs. Though there is no precise method for measurement of spirituality, Flannelly and Inouye (2001) discovered that religion and spirituality may be positively correlated with pleasure and quality of life. Interestingly, common causes of people’s miseries and worries include poverty, dependency upon children in old age, extended and untreated medical problems, use of violence, and abuse within family and lack of internal peace. (Pirani et al., 2008). These miseries of life produce medical complications physically and mentally (Glik, 1988). In such circumstances, people do go to doctors/hospitals for treatment but end up finding consolation in spiritual healing at Dargahs (Golomb, 1985). Visiting Dargahs is more mental than physical (Rhi, 2001).

Dargahs provide more space to women to get mental and spiritual peace

Women can be found more involved than men in ritual practising at Dargahs. Due to its rituals and literary behaviours, Dargahs also provide an open space for females to actively participate in the sacred (Abbas, 2003). Eaton says that females are acknowledged as the most enthusiastic partakers in widespread Sufi traditions of South Asia (Eaton, 1974; Gottschalk, 2006). Otherwise performing restricted roles in the religious affairs, women find catharsis in the Dargah rituals, for they allow them to express their emotional, material and spiritual needs and to seek their redresses (Mazumdar & Mazumdar, 2002).

Conclusion

Sufi Dargahs hold immense position in the society of Pakistan generally and in the Punjab particularly. The character of Sufis has been considered as intercessor that directed to Allah and finally attainment of happiness. The major objective of paying visits to Dargahs is the fulfillment of the desires based upon social, financial, political, religious, physical, mental and mystical aspects of the visitors’ life. Also, a majority of visitors visit Dargahs owing to their devotion and reverence for the Sufi/s. The results shows that majority of the visitors have firm belief that they would get inner satisfaction and mental peace after their desires are fulfilled. The result of the study also demonstrates that the satisfaction which devotees and visitors at both Chishti Dargahs get after performing various rituals proves their high level of trust in both Chishti Sufis that ultimately makes both Chishti Dargahs living bodies in today’s world even after the demise of both Sufis centuries ago.

References

Abbas, S. B. (2003). The female voice in Sufi ritual: Devotional practices of Pakistan and India. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Abbas, S., Qureshi, S., Safdar, R., & Zakar, R. (2013). Peoples’ perceptions about visiting Sufi shrine in Pakistan. A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, 28(2), 369–387. Retrieved from http://results.pu.

edu.pk/images/journal/csas/PDF/10%20Safdar%20Abbas_v28_2_13.pdf

Al-Hujwīrī, Alī ibn ‘Uthmān. (1911/1976). Kashf al-Mahjūb. (R. A. Nicholson, Trans.). Lahore: Islamic Book Foundation.

Anjum, T. (2011). Chishti Sufis in the Sultanate of Delhi (1190–1400): From restrained indifference to calculated defiance. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Armstrong, A. (2001). Sufi terminology: Al-Qamus Al-Sufi, the mystical language of Islam. Lahore:Ferozsons (Pvt.) Ltd.

Aulia, N. u. D. (1985). Rahat ul Qaloob [The peace of hearts]. (M. W. Dehlvi, Trans.). Lahore: Zia ul Quran Publications.

Bell, C. (1997). Ritual: Perspectives and dimensions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, J. (1998). The power of myth. Betty Sue flower. New York, NY: Apostrophe S Productions, Inc.

Chaghatai, M. I. (Ed.). (2006). Baba Ji, life and teachings of Farid-ud-Din Ganj-i-Shakar. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications.

Chaudhry, H.-u.-R. (2013). Saints and shrines in Pakistan: Anthropological perspective. Islamabad: National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Center of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University.

David, E. J. (2007). Introducing anthropology of religion culture to the ultimate. New York, NY:Routledge.

Dehlavī, A. H. ‘A. S. (1990/1992). Fawā’id al-Fu’ād. Delhi: Urdu Academy.

Eaton, R. M. (1974). Sufi folk literature and the expansion of Indian Islam. History of Religions, 14(2), 117–127. doi:10.1086/462718

Encyclopædia Britannica. (2017). Punjab, Province of Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/place/Punjab-province-Pakistan

Farooq, A., & Kayani, A. K. (2012). Prevalence of superstitions and other supernatural in rural Punjab: A sociological perspective. A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, 27(2), 335–344. Retrieved from

Flannelly, L. T., & Inouye, J. (2001). Relationships of religion, health status, and socioeconomic status to the quality of life of individuals who are HIV positive. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 253– 272. doi:10.1080/01612840152053093

Fleiderer, B. P. (1988). The semiotics of ritual healing in a North Indian Muslim shrine. Social Science & Medicine, 27, 417–424. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90364-4

Frembgen, J. W. (2004). From dervish to saint: Constructing charisma in contemporary Pakistani Sufism. The Muslim World, 92(2), 255. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2004.00050.x

Glik, D. C. (1988). Symbolic, ritual and social dynamics of spiritual healing. Social Science & Medicine, 27, 1197–1206. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(88)90349-8

Golomb, L. (1985). Curing and sociocultural separatism in south Thailand. Social Science & Medicine, 21(4), 463–468. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(85)90226-6

Gottschalk, P. (Ed.). (2006). Indian Muslim tradition. In G. Thursby & S. Mittal (Eds.), Religions of south Asia: An introduction (pp. 201–245). London: Routledge.

Haeri, M. (2000). The Chishtis: A living light. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hassan, R. (1987). Religion, society, and the state in Pakistan: Pirs and politics. Asian Survey, 27(5), 552–565. doi:10.2307/2644855

Husain, N., Chaudhry, I. B., Afridi, M. A., Tomenson, B., & Creed, F. (2007). Life stress and depression in a tribal area of Pakistan. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 36–41. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022913

Islam, R. (2002). Sufism in South Asia: Impact on fourteenth century Muslim society. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Juergen, F. (1998). The Majzub Mama Ji Sarkar: A friend of God moves from one house to another. In P. Werbner & H. Basu (Eds.), Embodying charisma: Modernity, locality and the performance of emotion in Sufi cults (pp. 140–159). London: Routledge.

Khan, S., & Sajid, M. R. (2011). The essence of shrines in rural Punjab: A case study of the shrines at Barrilla sharif, Gujrat-Pakistan. Humanity and Social Sciences Journal, 6(1), 66–77. Retrieved from https://www.idosi.org/hssj/hssj6(1)11/10.pdf

Khanam, F. (2009). Sufism: An introduction. New Delhi: Goodword Books.

Khurd, S. M. i. M. ‘A. K. a. A. (1885). Siyar al-Awliyā [Biographies of saints]. Delhi: Muhibb-i Hind Press.

Kurin, R. (1983). The structure of blessedness at a Muslim shrine in Pakistan. Middle Eastern Studies, 19 (3), 312–325. doi:10.1080/00263208308700553

Levin, J. (2008). Esoteric healing traditions: A conceptual overview. The Journal of Science and Healing, 4(2), 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2007.12.003

Lwise, P. (1985). Pirs, shrines and Pakistani Islam. Rawalpindi: Christian Study Center.

Malik, S. J. (1990). Change in traditional institutions: Waqf in Pakistan. Die Welt des Islams, 30(1), 63–97. doi:10.2307/1571046

Mazumdar, S., & Mazumbar, S. (2002). In mosques and shrines: Women’s agency in public sacred space. Journal of Ritual Studies, 16(2), 165–179. Retrieved from https://sites.la.utexas.edu/ritualstudies-group/in-mosques-and-shrines-womens-agency-in-public-sacred-space-shampa-mazumdarand-sanjoy-mazumdar/

Myerhoff, B. (1997). Secular ritual. Amsterdam: Van Gorcum.

Nizami, K. A. (2007). Tarıkh-e-Mashaıekh-e-Chisht [The history of Chishti Sufi masters] (Vols. 1–5). Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Pemberton, K. (2002). Islamic and Islamicizing discourses: Ritual performance, didactic texts, and the reformist challenge in the south Asian Sufi Milieu. Annual of Urdu Studies, 17, 55–83. Retrieved from http://www.urdustudies.com/pdf/17/09_Pemberton.pdf

Penner, H. H. (2017). Ritual. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/ritual

Pirani, F. M., Papadopoulos, R., Foster, J., & Leavey, G. (2008). I will accept whatever is meant for us. I wait for that – day and night: The search for healing at a Muslim shrine in Pakistan. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(4), 375–386. doi:10.1080/13674670701482695

Raj, S. J., & Harman, W. P. (Eds.). (2006). Dealing with deities: The ritual vow in South Asia. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Rehman, U. (2006). Religion, politics and holy shrines in Pakistan. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 19(2), 17–28. Retrieved from https://www.idunn.no/file/ci/66930427/Religion_Politics_And_Holy_Shrines_In_Pakistan.pdf

Rhi, B. Y. (2001). Culture, spirituality, and mental health: The forgotten aspects of religion and health.

Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(3), 569–579. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70248-3

Sanat. (2017). The role of music and dance in Sufistic ritual practice. Retrieved from http://www.sanat.

orexca.com/eng/2-08/roleofmusic.shtml

Schimmel, A. (1982). Islam in India and Pakistan. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Schimmel, A. (1985). And Muhammad is his messenger: The veneration of the Prophet in Islamic piety.

Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Schimmel, A. (2003). Mystical dimension of Islam. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications.

Schultz, E. A., & Lavenda, R. H. (2009). Cultural anthropology (7th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sosis, R., & Alcorta, C. (2003). Signaling, solidarity and the sacred: The evolution of religious behavior.

Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 12, 264–274. doi:10.1002/evan.10120

Vandal, S. H. (2011). Cultural expressions of south Punjab. Islamabad: Thaap Publications.

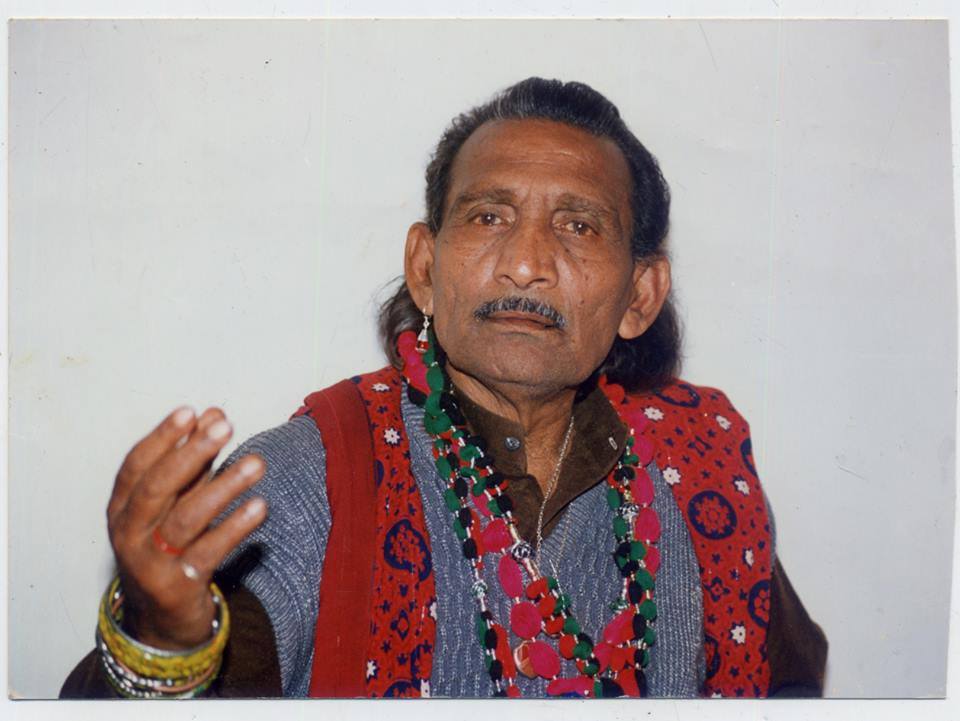

Picture Credits- Mr. Bandeep Singh

Guest Authors

- Aatif Kazmi

- Absar Balkhi

- Afzal Muhammad Farooqui Safvi

- Ahmad Raza Ashrafi

- Ahmer Raza

- Akhlaque Ahan

- Arun Prakash Ray

- Balram Shukla

- Dr. Kabeeruddin Khan Warsi

- Dr. Shamim Munemi

- Faiz Ali Shah

- Farhat Ehsas

- Iltefat Amjadi

- Jabir Khan Warsi

- Junaid Ahmad Noor

- Kaleem Athar

- Khursheed Alam

- Mazhar Farid

- Meher Murshed

- Mustaquim Pervez

- Qurban Ali

- Raiyan Abulolai

- Rekha Pande

- Saabir Raza Rahbar Misbahi

- Shamim Tariq

- Sharid Ansari

- Shashi Tandon

- Sufinama Archive

- Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

- Syed Moin Alvi

- Syed Rizwanullah Wahidi

- Syed Shah Tariq Enayatullah Firdausi

- Umair Husami

- Yusuf Shahab

- Zafarullah Ansari

- Zunnoorain Alavi