Basant: The day hope lived in Nizamuddin Auliya again

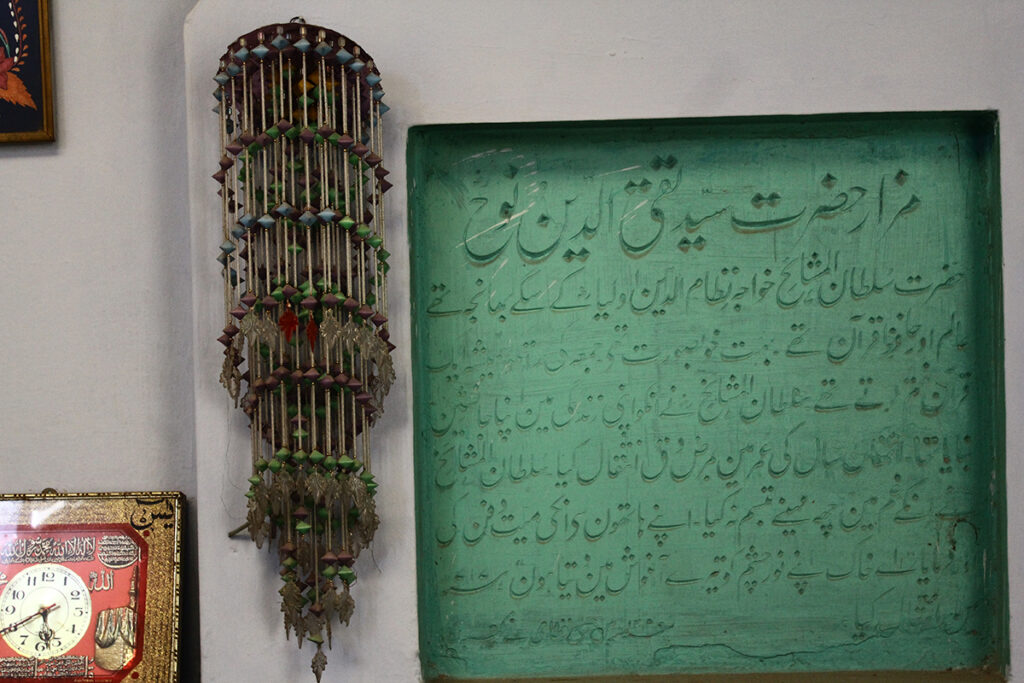

There was a day when hope died in Nizamuddin Auliya’s khanqah. That was the day he buried his nephew Taqiuddin Nuh, the apple of his eye, quite like his favourite disciple, Amir Khusro, court poet of the sultans of Delhi and master musician.

pic -Aalok Sony

pic- Aalok Sony

The master grieved. He had not known grief such as this; this dark; this enveloping; this debilitating; this ravaging. And he had befriended grief many a time.

Nizamuddin’s grandparents had fled Bukhara, leaving behind all their riches when Chinghiz Khan sacked the city. They settled in Badaun. Soon after Nizamuddin was born, his mother, Bibi Zuleikha, had a dream. She heard a voice, saying she must choose between her husband or son as one of them was destined to die. She said Nizamuddin should live. Nizamuddin’s father, Khwaja Ahmad, fell ill soon after and passed away.

Bibi Zuleikha, a pious woman, raised her children, Nizamuddin and his sister Zainab, amidst grinding poverty. On many a day, there would be no food at home; they would be the guests of God. But their mother instilled in them trust. That trust would be his anchor.

If his mother taught him trust, Nizamuddin’s master, Shaikh Farid, taught him patience. That patience would be tested when he returned from Pakpattan after learning the ways of a mystic from Shaikh Farid.

Nizamuddin searched for a home. Bibi Zuleikha’s health was failing. She looked at his feet one day and predicted that he would become a man of destiny after she had passed. The new moon was born again and Nizamuddin placed his head at her feet as he did each time. “Nizam, at whose feet will you place your head next month?” Nizamuddin wept. He knew what she was saying. He knew her words would come true.

“Whose care will you entrust me to?” he asked. Bibi Zuleikha said: “I will tell you tomorrow. Go and sleep in Shaikh Najeebuddin’s (Najeebuddin Mutawakil, Baba Farid’s brother) house tonight.”

As dawn broke, Nizamuddin was awoken. His mother was calling. “Where is your right hand?” she asked. Nizamuddin extended it. She grasped his hand and said: “God, I entrust him to You.”

Mai Sahiba lies in a grave next to the room she lived in, a short distance from the Qutb Minar.

Nizamuddin, in his early twenties, had buried a part of his soul: his mother. She was his life. She was his everything. For when there was nothing, no food, no home, she was there to offer him comfort; she was there to reinforce trust.

And it was that cradle; his mother’s loving arms that helped Nizamuddin overcome his grief — for she was always there when he needed her.

Remember the time when sultan Mubarak Shah wanted Nizamuddin dead.

On the first day of the new moon, all the nobles and ulema had to offer their respects to the sultan. Nizamuddin did not bother paying obeisance to the mighty Alauddin Khilji, he was certainly not going to entertain Mubarak Shah. Instead, Nizamuddin sent his trusted attendant Iqbal or Lalla to the court. The sultan was incensed. He sent word that he would punish Nizamuddin if he did not come to pay his respects at the next new moon. But this was Nizamuddin. He would not budge.

Nizamuddin went to his mother Mai Sahiba’s grave and prayed: “If the sultan’s life does not end by the first of the next lunar month, I won’t be able to come to see you again.”

The new moon day arrived. Nizamuddin’s disciples were terrified. They went to their master. He seemed unperturbed. “Last night, I saw in my dream a bull rushing at me. I caught its horns and pushed it back,”

Nizamuddin said. The disciples were calm. They interpreted the dream: no harm would come to their master. But Iqbal, his attendant, was on edge. He asked his master twice if he should ready the palanquin so that they could proceed towards the palace. “Do something else,” Nizamuddin said.

And minutes later, there was word from the palace: Mubarak Shah had been slaughtered. One of his favoured generals, Khusro Shah, had marched into the palace. He caught the sultan by the hair, and one of his men, Jaharia, stabbed him.The early days of a dervish weren’t easy for Nizamuddin. There were days when he would have to go without food. Once three days had passed without him having eaten. And then someone handed him khichri. “Nothing in life tasted better,” he would reminisce.

Nizamuddin started enrolling a few disciples and all went hungry when there was nothing to eat. There was a woman in the neighbourhood who earned a living by spinning thread. She would bake bread at iftar. She once heard that Nizamuddin and his disciples had been starving for four days straight. The woman sent them some flour she had saved. Nizamuddin asked one of his disciples to mix it with water and put it to boil. It had not been fully baked when a dervish suddenly appeared and shouted: “If you have anything to eat, do not hold it from me.”

Nizamuddin asked him to wait because the bread had not baked. The dervish grew impatient, and Nizamuddin, rolling his sleeves, brought the boiling pot before the dervish. He picked up the pot and smashed it to the ground. “Shaikh Farid has bestowed spiritual blessings on Shaikh Nizamuddin. I break the vessel of his material poverty,” the dervish said as he left.

From that day on, futuh or unasked for gifts, flooded Nizamuddin’s khanqah. Whatever came as futuh was distributed among the needy. Nothing was ever stored because that would show Nizamuddin didn’t have trust. His disciples grew and the poor came in hundreds every day. No one left hungry from his khanqah in Ghiyaspur. Nizamuddin knew poverty well. He had gone hungry too.

pic-Aalok Sony

Despite the many times grief had befriended him; despite the abject poverty; the evil designs of the sultans against him and the difficult times, Nizamuddin always smiled. He had a tremendous sense of humour.

Once a man decided to join his friends who were going to see Nizamuddin. Since everyone was carrying something, he too decided he needed to take a gift to keep up appearances. But he wasn’t going to take the trouble to look for an appropriate token; he wrapped some mud into a packet, convincing himself that Nizamuddin wouldn’t open every gift. His disciples and attendants would take them away. And so the delegation trooped into the khanqah and placed their offerings before the Shaikh. As the man guessed, the disciples collected the gifts to be distributed among the poor. When they picked up his packet, Nizamuddin stopped them. “Let me take a look at this special gift. My friend has brought me collyrium for my eyes.”

This was a man who had forsaken a life of comfort for the service of the poor for in doing that he lived for the Lord alone. This was a man who said you cannot place thorns in the path of your foes only roses. This was the man whose heart went out to the woman drawing water from the well when the Jamuna was flowing close by because river water whetted their appetites and she and her husband were too poor to afford a regular supply of food. He ensured they never went hungry. This was a fakir who was the most erudite scholar of his times. This was a fakir to whose door the nobleman and beggar flocked. This was a fakir who had no time for kings. It bordered on contempt for what the kings stood for, but this fakir had no time for contempt as well. Every second of his existence, every pore of his being the fakir spent in serving the poor because in their eyes he saw his Lord.

But those eyes had lost their lustre the day he buried his young nephew Taqiuddin Nuh, a pious boy, drawn to spirituality.

Nizamuddin grieved. He became withdrawn; he would not speak. His disciples were worried. They had never seen their master this way. Even Amir Khusro, who conjured up joy in the master’s face, did not have the magic up his sleeve to cure the depression. Until one day. He saw a group of women, dressed in yellow, dancing and singing their way to a temple. He stopped them and asked what they were doing. Celebrating Basant, they replied. The courtier dressed up like the women in yellow and went dancing and singing to his master. Nizamuddin smiled.

pic- Aalok Sony

Every year, Basant or the onset of Spring is celebrated at Nizamuddin’s shrine to mark the day Khusro got the master’s smile back. Hope lived again.

Today, Basant is being celebrated at his shrine. In this courtyard of love, religion doesn’t matter. Just faith. Come, come, whoever you are,

Wanderer, worshipper, lover of leaving,

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Even if you have broken your vows a thousand times,

It doesn’t matter,

Come, come yet again, come.

Some attribute this verse to Rumi; some to Shaikh Abu Said Abul Khair.

Nizamuddin Auliya would often quote this saying by Shaikh Abu Said:

“There are as many paths as there are grains of sand.”

There is a path that leads to Nizamuddin Auliya’s courtyard of love. It is always enveloped by hope and the fragrance of Spring.

Guest Authors

- Aatif Kazmi

- Absar Balkhi

- Afzal Muhammad Farooqui Safvi

- Ahmad Raza Ashrafi

- Ahmer Raza

- Akhlaque Ahan

- Arun Prakash Ray

- Balram Shukla

- Dr. Kabeeruddin Khan Warsi

- Faiz Ali Shah

- Farhat Ehsas

- Iltefat Amjadi

- Jabir Khan Warsi

- Junaid Ahmad Noor

- Kaleem Athar

- Khursheed Alam

- Mazhar Farid

- Meher Murshed

- Mustaquim Pervez

- Qurban Ali

- Raiyan Abulolai

- Rekha Pande

- Saabir Raza Rahbar Misbahi

- Shamim Tariq

- Sharid Ansari

- Shashi Tandon

- Sufinama Archive

- Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

- Syed Moin Alvi

- Syed Rizwanullah Wahidi

- Syed Shah Shamimuddin Ahmad Munemi

- Syed Shah Tariq Enayatullah Firdausi

- Umair Husami

- Yusuf Shahab

- Zafarullah Ansari

- Zunnoorain Alavi