Baba Farid: Bringing happiness to the human heart

I wish always to live in longing for You.

May I become dust, dwelling under your Feet.

My goal freed of both worlds is only You.

I die for you, just as I live for You.

Baba Farid

It was sometime around 1264, young Nizamuddin Auliya wandered into a desert in the depths of depression. How would he live now? For years he had nurtured just one desire: to find Baba Farid and place his head at his feet.

He had excelled in his studies overcoming hunger and poverty. Nizamuddin could have become a judge. He would have had fame, money and respect in Delhi. He would never have to go hungry again. His mother, Bibi Zuleikha, would have seen happier days. But he gave all that up. He would go hungry again; live in desperate poverty — all to serve Baba Farid and his Maker.

But now life had no meaning. How could it have come to this?

Would Baba Farid’s rage ebb?

Would Baba Farid forgive him?

Baba Farid was born in 1175 when Mohammad Ghori raided Multan. His grandfather, Shoaib, fled Kabul when the ambitions of the Turks became more of a harangue. Shoaib settled in Kahtwal, now in Pakistan, and was appointed as a judge by the sultan. He married his son, Jamaluddin Sulaiman, to Qarsum Bibi, the daughter of Shaikh Wajiddun Khojendi. The couple had three sons — Izzuddin Mahmood, the eldest, Fariduddin and Najeebuddin Mutawakil.

Ever since he was a child Farid was different. He would say his prayers, and his mother, a pious lady, would give him sugar, which he loved. Once the great Sufi Shaikh, Jalaluddin Tabrizi, was passing through Kahtwal on his way to Delhi. As he entered the town, he asked if there was a mystic living there. There was something in the air. Town folk said there was no one, but a boy, Fariduddin, who was lost in prayer in the mosque. Jalaluddin had to see him. Someone gave him a pomegranate, which he took as a gift for Farid. Jalaluddin broke half and handed the boy the pomegranate. Farid politely refused. He was fasting. Jalaluddin left.

Later, Farid found a seed that had dropped on the ground and wrapped it up in his handkerchief. At iftar, when he ended his fast, he ate the seed. He felt a sense of enlightenment. He knew he had been blessed.

Farid was a diligent student and his pursuit of academics took him to Multan at the age of 18. He was reading a book on law in a mosque when a man entered and began to say his prayers. Farid was in awe. He could sense his spirituality. The man finished his prayers, turned to Farid and asked what he was reading. ‘It is law,’ Farid replied.

Farid placed his head at the man’s feet.

The great Saint of Ajmer, Moinuddin Chishti, who introduced Chishti Sufism to the Indian subcontinent, had made Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki his successor. Farid had just made Qutbuddin his master and followed him to Delhi.

There, at his khanqah, Qutbuddin gave Farid a small room. Farid prayed and fasted. Moinuddin Chishti came to Delhi on a visit and saw Farid. Garib Nawaz knew he was different. Like Jalaluddin Tabrizi, who had offered Farid a pomegranate, he could sense it. When Chishti and Qutbuddin Kaki went to Farid’s room, he was emaciated, having fasted for days. As they entered, Farid tried to get up, but could not. With tears in his eyes, Farid placed his head at their feet. They blessed him.

Baba Farid later told his master about the pomegranate seed and wished that he had taken the entire fruit from Jalaluddin Tabrizi. His blessings would have multiplied. Qutbuddin Kaki replied the seed was destined for Baba Farid and it contained all the blessings. There was no need for the entire fruit. Chishti Sufis always eat an entire pomegranate — the sacred seed must not escape them.

Ganj-e-Shakar – The Treasury of Sugar

Chishti Sufis fasted and put themselves through penitence to shut the world out to commune with the Maker. Baba Farid, like no other Chishti, put himself through rigorous penitence. One day he asked Qutbuddin Kaki if he could perform the Chillah.

Qutbuddin Kaki said there was no need as it would just attract publicity and amount to showing off one’s devotion to God. Baba Farid said he was not hunting for fame and his master knew that. Qutbuddin Kaki replied, asking him to perform the Chillah-e-Makus. Farid did not know what that meant. He later learnt what it was — he had to tie his legs to the branch of a tree near a well and suspend himself into it. Farid had to do this for forty nights. It had to be done discreetly — away from the public eye. Delhi was certainly not the place. He arrived at Uchch.

There was a mosque, there was a well, which had a tree over it and there was a man, who called the faithful to prayer. Rashiduddin Mina’i, a native of Hansi, seemed he could keep a secret. Baba Farid kept a watchful eye on him for three days. He was satisfied with the man’s integrity. One day, after Isha prayer, Mina’i tied Farid’s legs with rope to a branch of the tree and suspended him into the well. He pulled him up just before dawn. For forty nights, Baba Farid remembered his Maker as he stared into the darkness around him and the depths of the darkness below. There was no fear of the branch breaking. He had conquered that. There was no fear of the night. He had trust.

Qutbuddin Kaki instilled the mystic principle of Tayy in Baba Farid, which meant he would have to fast for three days. He could only end his fast if food came from an unseen source. He fasted, but no food came. On the third day, a man gave him some bread. Baba Farid ate and almost instantly saw a kite with the intestines of some animal in its beak. He was repulsed. He threw up. Baba Farid told his master the story and Qutbuddin Kaki said God had intervened. The man who gave him the bread was a drunk. He asked him to fast again. For three days Baba Farid had nothing to eat. He grew weak, his stomach burned. Baba Farid picked up pebbles and put them into his mouth. They turned into sugar. He thought the devil was up to tricks and threw the pebbles away.

He was hungry. The time came for morning prayers. Farid said to himself if he didn’t eat, he wouldn’t be able to say them. He ate the pebbles. They turned to sugar. His mother would give him sugar as a child when he said his prayers.

Qutbuddin Kaki told him he had done right as he had eaten what came from the unknown. From that day on, Baba Farid became known as Ganj-e-Shakar or the Treasury of Sugar.

There are other accounts as well, which explain why he is known as Ganj-e-Shakar. Baba Farid was on his way to see Qutbuddin Kaki. He had fasted for seven days and was terribly weak. Baba Farid was wearing wooden sandals. The road was muddy from rain. He slipped and mud went into his mouth. It turned to sugar.

Once a merchant came to him, carrying sugar in sacks. Baba Farid asked what was in them. Fearing he might want some, the merchant said salt. Then let it be salt, Baba Farid replied. The merchant opened the sacks later to find salt. He went to Baba Farid and asked to be pardoned and that the salt be made sugar. Baba Farid prayed. There was sugar.

His mother would place a packet of sugar under his pillow every night. The child would say his prayers in the morning and find the sugar. Qarsum Bibi stopped placing sugar under his pillow when he turned 12. But when Baba Farid said his prayers in the morning, he always got his packet.

Baba Farid lived the life of a mystic, lost in the love of his Maker, for more than seventy years. He looked after the poor, the hungry and the destitute. No one left his door hungry. No one left his house with a troubled soul. He realised his Maker by serving the needy. His religion was bringing happiness to the human heart.

But he had to find a successor to carry on the work of Chishti Sufis. He was waiting for Nizamuddin.

A wandering minstrel, Abu Bakr Kharrat, came to Badaon, to see Nizamuddin’s teacher. He praised Bahauddin Zakariya, a Sufi master of the Suhrawardi sect in Multan, and then spoke of his visit to Baba Farid. For some inexplicable reason, Baba Farid lived in Nizamuddin’s heart.

Eight years later, Nizamuddin made the journey to Ajodhan, Pakpattan. Baba Farid knew he was coming. It was destined.

The 90-year-old Sufi Shaikh noticed Nizamuddin was trembling with awe. He welcomed Nizamuddin with these words: “The fire of your separation has burnt many hearts. The storm of desire to meet you has ravaged many lives.”

Nizamuddin mustered up the courage to say he wanted to kiss his feet. Baba Farid knew he was tense. “Every newcomer is nervous,” he said as he soothed Nizamuddin’s mind.

One of the reasons Nizamuddin was now in Ajodhan was because of Baba Farid’s brother, Najeebuddin Mutawakil, who lived in the same locality in Delhi. Nizamuddin on completing his studies had implored Najeebuddin to read the Surat Al Fatiha as a blessing so he could become a judge and be held in high esteem. Najeebuddin said nothing to Nizamuddin, but on being asked again, he remarked: “Don’t be a judge, be something else.”

It was that night in Delhi when Nizamuddin was lost in prayer that the muezzin recited a verse from the Quran asking believers to remember God. It was that one moment of revelation. Nizamuddin had to go to Shaikh Farid.

The student placed his head at his master’s feet.

Baba Farid welcomed him as a father would a son who he had not seen for years. He gave him a cot to sleep on in his khanqah while all the other disciples, even the senior ones, slept on the floor. New disciples to the khanqah had to get their heads shaved as an initiation practice. Nizamuddin had long, black curls of hair and was fond of his locks. He did not want to get rid of them. And Baba Farid’s intuitive mind knew that. Nizamuddin was just 20. Baba Farid humoured his fancy. He did not ask Nizamuddin to shave his head. But the student, devoted to his master, saw all the others had, and he too followed suit after taking Baba Farid’s permission.

Now in that desert, as he wandered aimlessly in the depths of depression, Nizamuddin thought Baba Farid’s welcome had seemed almost unreal. But this was unreal too. How could Nizamuddin live after this? His life flashed past.

The lessons a Sufi learns

His master was tough. Nizamuddin knew that. Everyone in the khanqah was assigned various chores. Nizamuddin’s responsibility was to boil a broth of wild fruits. Baba Farid and his disciples led a life of poverty. Whatever food came as futuh or unasked for gifts, Baba Farid distributed amongst the poor. He never kept anything for the next day, as it would show he had no trust in God to provide. When there was no futuh, they ate broth made of wild fruit. Nizamuddin was boiling the broth, when he found there was no salt in the kitchen. He went to the grocer and bought some salt on credit since he had no money. He placed the broth before his master.

Baba Farid put his hand into the broth and stopped. “My hand has become heavy. Perhaps, there is something in it that I am not permitted to put a morsel in my mouth,” he said. Nizamuddin trembled. He placed his head on the ground and said: “My master, Jalal, Badruddin Ishaq and Husamuddin bring wood, wild fruit and water for the kitchen. This man boils the wild fruit and prepares the broth. He brings it before his master. There seems nothing to doubt. The master knows that.”

Baba Farid asked about the salt. Nizamuddin placed his head on the ground again and told him how he had got it. “Dervishes prefer to die of starvation rather than incur debt to satisfy their desires. Debt and resignation are poles apart and cannot co-exist,” Baba Farid said. He did not touch the broth.

There was a time Nizamuddin’s classmate came to Ajodhan and stayed in an inn with his servant. He saw Nizamuddin in Baba Farid’s khanqah living a life of poverty in tattered clothes, learning the life of a Chishti mystic devoted to realising God by serving the poor. His friend exclaimed: “Nizamuddin! What misfortune has befallen you? Had you taken up the job of a judge in Delhi, you would have become a leading scholar and made money.” Nizamuddin said nothing, but told his master the story. “What would be your answer to such a question?” Baba Farid asked. “As the Shaikh directs,” Nizamuddin replied.

“When you meet him recite this couplet: ‘You are not my travelling companion. Seek your own path. Get along. May prosperity be your portion in life and misfortune mine,’” the master said.

Baba Farid asked Nizamuddin to take a tray of food from the kitchen and carry it on his head to his friend. Nizamuddin’s classmate became Baba Farid’s disciple. The master’s teachings and the way he had lived his life had made Nizamuddin love and respect him even more. But an innocent remark had ruined it all.

The master was teaching Shaikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi’s Awarif Al Ma’arif, regarded as a manual for Sufis wanting to set up a khanqah and enroll disciples, when he faltered. The copy of Awarif Al Ma’arif Baba Farid had was unclear in parts. He had to proceed slowly as he came across the tricky lines. Nizamuddin piped up and said Baba Farid’s brother in Delhi, Najeebuddin Mutawakil, had a clear copy. Baba Farid was enraged. “Has this dervish no capacity to correct a defective manuscript?” he shouted repeatedly.

Nizamuddin remembered the incident even forty years later when he was talking to people who came to see him. Nizamuddin’s disciple and court poet Amir Hasan Sijzi took down the words he spoke at these assemblies. He later compiled the teachings into a book in Persian called Fawaid Al Fuad.

“The first one or two times these words came to his blessed lips I did not know to whom he was speaking. If I had realised he was referring to me, I would have immediately implored his forgiveness,” Nizamuddin said.

But Baba Farid’s torrent of anger continued for an hour. He repeated the same line: “Has this dervish no capacity to correct a defective manuscript?”

Nizamuddin recounted: “Badruddin Ishaq — may God grant him mercy and forgiveness — turned towards me: ‘The Shaikh is addressing this remark to you.’ “I rose, bared my head and threw myself at the Shaikh’s feet. ‘As God is my witness, I had not realised that the esteemed master was referring to me in this question. I had seen another manuscript and was reporting the fact; I had absolutely nothing else in mind.”’

“But, however, much I apologised, I saw that it did not diminish the Shaikh’s rage. When at last I arose from there, I did not know what I was doing or where I was going. May it never happen that anyone else experiences the anguish that befell me that day. Tears overwhelmed me. Distraught and bewildered, I walked around until I arrived at the edge of a well. I thought to myself, better to be a dead beggar than to go on living with the bad name that this indiscretion has given me. In this state of anxiety and confusion, I wandered towards the desert, weeping and lamenting. Only God Almighty knows what state had overcome me at that moment,” Nizamuddin recalled.

The one man whom he had treasured and respected he had alienated by a remark that seemed innocuous. Baba Farid’s son, Shihabuddin, who had become fond of Nizamuddin, was disturbed at what had transpired. He approached his father, asking him to forgive Nizamuddin.

A Sufi has no arrogance

The master summoned him. Nizamuddin came and placed his head at his feet. The Shaikh was pleased. “The next day, summoning me to his presence, he showered me with words of compassion and comfort: ‘I have done all this for the perfection of your spiritual state.’ He ordered that I be presented with a robe of honour and special clothes. Praise be to God, the Lord of the universe!”

Baba Farid’s temper can seem to be harsh, but he had detected a streak of intellectual superiority in Nizamuddin, the arrogance that can accompany academic brilliance. And, the master had to purge that out of his system. There was no room for ego, no space for superiority if Nizamuddin was going to serve people and bring happiness to the human heart.

If Baba Farid was tough, he was forgiving.

Amir Hasan once asked Nizamuddin: “Did they not perpetrate magic against Shaikh Fariduddin — may God sanctify his lofty secret?” “Yes,” Nizamuddin replied. “He repelled that magic, and they apprehended the group who perpetrated it.”’

Baba Farid fell ill and did not eat for days. His disciples were worried. Doctors could not diagnose the illness. His conditioned worsened day by day. He called his son, Badruddin Sulaiman, and Nizamuddin and asked them to pray for his recovery. That night, an old man came to Badruddin Sulaiman’s dreams. “Your father is a victim of magic.” He asked who had done it. The old man replied the son of the magician, Shihabuddin. Badruddin Sulaiman asked the old man how Baba Farid could be cured. He told him to say a prayer as he sat by Shihabuddin’s grave.

The next morning, he related his dream to his father. Baba Farid asked Nizamuddin to memorise the prayer and recite it at Shihabuddin’s grave. The magician was well-known in Ajodhan. Nizamuddin found his grave. As he prayed, he removed the earth from above the cenotaph of the grave. He found a small human statute made of flour with a horse’s hair tied around it. Needles had been stuck on the statue. Nizamuddin brought the statue to Baba Farid. He told him to take the needles out and remove the hair. As he drew the needles out, one by one, Baba Farid got better. The statue was thrown in the river.

The governor of Ajodhan heard about the matter and was incensed. He arrested Shihabuddin’s son and sent him in chains to Baba Farid. “This man deserves death. If you permit me, I shall put him to death,” the governor said. “God has given me health. I forgive him in gratitude for my recovery. You should also overlook his wrong,” Baba Farid said.

Nizamuddin recounted another story. “One day, Shaikh Al Islam Fariduddin — may God sanctify his lofty secret — had just finished saying his morning prayer. Still engrossed in God, his head remained like that, absorbed in God, his head prostrate on the ground. But because it was winter they had brought a garment and spread it over his blessed body. No attendants remained. Just I and he and no one else. Suddenly someone entered and in a loud voice shouted ‘Peace!’ The Shaikh was jolted from his meditative mood. But with his head still prostrate on the ground and the garment covering him, he asked: ‘Who is here?’ I spoke up and said: ‘I am!’ ‘The man who just entered,’ said the Shaikh, ‘is a Turk of medium stature with a sallow complexion.’ I looked at that man. He was exactly as the Shaikh described him. I said: ‘Yes, he is.’ ‘Does he have a chain around his waist?’ I looked at him, and saw that he did. ‘Yes, he has,’ I replied. ‘And also does he have something in his ears?’ I looked and saw that he did. ‘Yes, he has an earring,’ I replied. And every time I looked at him and then responded to the Shaikh, the man became more and more uneasy. After I said ‘Yes, he has an earring,’ the Shaikh replied: ‘Tell him to go away lest he become disgraced.’ When I looked back toward the man, he had already taken to his heels and disappeared.”

You will not go to the doors of kings

Baba Farid like Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti and his master Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki did not associate with kings and courtiers.

A Sufi named Sayyidi Maula once stayed in Ajodhan with Baba Farid. He decided to leave for Delhi. Baba Farid cautioned him, saying he must not mix with nobles. “You are going to Delhi and wish to keep an open door and earn fame and honour. You know well what is good for you. But keep in mind one advice of mine. Do not mix with kings and courtiers. Consider their visits to your house as calamitous. A saint who opens the door of association with kings and courtiers is doomed,” Baba Farid said.

Sayyidi Maula went to Delhi and set up a big khanqah, where he fed thousands daily. The nobles of the sultan Jalaluddin Khilji’s court also paid him obeisance. These were the courtiers who were growing weary of sultan Jalaluddin’s weak rule. Rumours spread in Delhi that the courtiers would murder Jalaluddin and place Sayyidi Maula on the throne.

The sultan arrested Sayyidi Maula and his followers. He started arguing with Sayyidi Maula and in a fit of rage got an elephant to trample him. As Sayyidi was dying, a fanatic ripped him up with a razor, slashing his body over and over again before driving a knife into his body. A massive storm hit Delhi as life ebbed away from Sayyidi Maula. The sultan had him mangled on a rumour.

The Dervish of hope

Nizamuddin had visited his master thrice in his lifetime. Baba Farid had granted him the right to enroll disciples. While conferring the right or Khilafat Namah, Baba Farid said this to Nizamuddin: “You will be a tree under whose soothing shade people will find comfort.”

Nizamuddin was taken aback. This was a massive responsibility he could not shoulder. Baba Farid understood Nizamuddin was hesitant and said he would do well in his task. Nizamuddin was still concerned, and his master reassured him with conviction: “Nizam! Take it from me, though I do not know if I will be honoured before the Almighty or not, I promise not to enter Paradise without your disciples in my company.”

Baba Farid spent more than 70 years giving hope to the hapless, feeding the hungry and providing happiness to the human heart. He was in his nineties and his health had begun to break down.

It was 1265 when Syed Mohammad Kirmani better known as Amir Khurd, the author of Siyar-ul-Auliya, reached Ajodhan from Nizamuddin’s khanqah in Delhi. Baba Farid’s health had given way. It was a matter of time when the 91-year-old man who had headed the Chishti sect of Sufis for decades, would be reunited with the one love of his life, his Maker.

He lay weak in his cot in his little room. Outside, his sons worried who would be his successor. Amir Khurd wanted to pay his respects to Baba Farid, but his sons said it was not the time to see him. He pushed the door of the room open and fell at Baba Farid’s feet. “How are you Syed? How and when did you come here?” Baba Farid asked. “This very moment,” replied Amir Khurd and thought to himself that he should convey Nizamuddin’s respects.

But he hesitated, thinking this would annoy Baba Farid’s sons. They knew that if Nizamuddin’s name was mentioned, Baba Farid would make him his successor. Instead, Amir Khurd talked about the other saints of Delhi and mentioned Nizamuddin’s name in passing, conveying his respects. At that very moment, Baba Farid handed his cloak, his staff and prayer mat to Amir Khurd, instructing him to give them to Nizamuddin. Baba Farid’s sons were stunned. They quarreled with Amir Khurd, accusing him of depriving them of things that were dear to them.

Baba Farid had predicted that Nizamuddin would not be next to him when he would pass just as he was absent when his master, Shaikh Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar, was reunited with his Maker. But Baba Farid wanted to see his own son, also named Nizamuddin, an army officer based in Patiali. His son saw his father in a dream and left for Ajodhan. “Nizamuddin is coming,” said Baba Farid. “But what is the use.”

Baba Farid rose to say the evening Isha prayer with the congregation. He soon fell unconscious. The khanqah was raw with grief. The emptiness was unbearable. Baba Farid woke up. “Have I offered my prayer?” Yes was the answer. “Let me offer them again. Who knows what is going to happen?” He said his prayers and fell unconscious again. Baba Farid woke a little later and asked the same question. He got the same answer. He offered his evening prayer for the third time and fell asleep forever, uttering: “Oh the Living and the Immortal.”

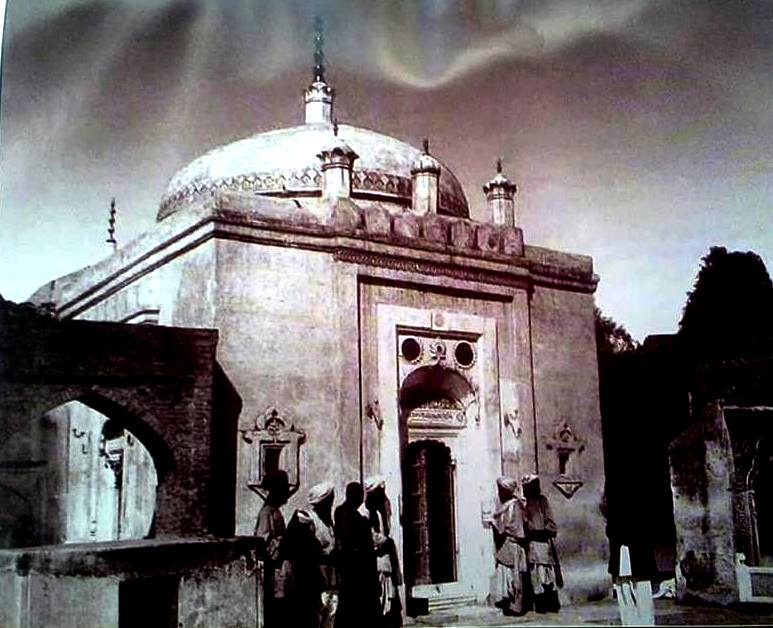

Baba Farid’s life was spent in poverty. He was offered the world, but he gave it all away to the poor. There was no money to buy a shroud. Amir Khurd’s grandmother gave a white sheet to cover his coffin. The door of Baba Farid’s hut was broken down — the unbaked bricks were used to construct the grave. The man who offered to make Baba Farid a pucca house, but whose offer was rejected by the saint, built a dome over the grave.

More than 750 years on Baba Farid’s house continues to feed the hungry and give hope to the hapless. It brings happiness to the human heart.

Meher Murshed is the author of Song of The Dervish, a book that details the lives of Nizamuddin Auliya and Amir Khusro. It recounts true stories of why people, cutting across religion, visit Nizamuddin Auliya’s dargah 700 years on. Meher is also a journalist. Twitter Account – https://twitter.com/mehermurshed

Guest Authors

- Aatif Kazmi

- Absar Balkhi

- Afzal Muhammad Farooqui Safvi

- Ahmad Raza Ashrafi

- Ahmer Raza

- Akhlaque Ahan

- Arun Prakash Ray

- Balram Shukla

- Dr. Kabeeruddin Khan Warsi

- Dr. Shamim Munemi

- Faiz Ali Shah

- Farhat Ehsas

- Iltefat Amjadi

- Jabir Khan Warsi

- Junaid Ahmad Noor

- Kaleem Athar

- Khursheed Alam

- Mazhar Farid

- Meher Murshed

- Mustaquim Pervez

- Qurban Ali

- Raiyan Abulolai

- Rekha Pande

- Saabir Raza Rahbar Misbahi

- Shamim Tariq

- Sharid Ansari

- Shashi Tandon

- Sufinama Archive

- Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

- Syed Moin Alvi

- Syed Rizwanullah Wahidi

- Syed Shah Tariq Enayatullah Firdausi

- Umair Husami

- Yusuf Shahab

- Zafarullah Ansari

- Zunnoorain Alavi