SARMAD: His Life And Quatrains –B.A. Hashmi

Sufinama Archive

May 7, 2020

Sufinama Archive

May 7, 2020

Persian poetry before the introduction of the mystic element was generally non-individualistic and objective. The Qasida was indeed developed on a rather elaborate scale, but it was poetry faked for mercenary ends. The Tashbib or the lyric prelude, even when it was adroitly tagged on to the rest of the Qasida seldom formed part of an organic whole. The Masnawi which came next, was but narrative poetry interspersed with descriptive passages. The Ghazal was more subjective but, fettered by the conventions of Muslim society, it assumed rather a depraved tone. The lover of the Arab poets was chivalrous, fearless and true, but the lover of Persian poetry sought his love through power or pelf or self-abasement.

The beloved in Arab poetry was a beautiful maiden, who admired manly courage and was jealous of her modesty, but the beloved of Persian poetry believed in tormenting the lover to get the most out of him.

Such in brief was the outlook of Persian poetry before the finer sensibilities of mystics transformed almost all the types of Persian poetry. Sufi thought was surcharged with love of Eternal Truth, of Eternal Beauty and of Eternal Goodness. The Almighty was the Beloved. No submission to His will could be interpreted as abject humiliation. The desire for His attainment could not be attributed to earthly passion, and between His lovers there existed not jealousy but a community of sentiment. Each one of His lovers wondered at and admired the great secret of His ‘manifest yet hidden beauty.’ No doubt the influence of philosophic thought tended to make early mystic poetry abstract ; but the subjective element was all the time wedded to the expression of such abstract ideas as ‘the Being the Soul, the why and wherefore of all existence.’

Along with the advent of mysticism, another type of Poetry came into its own. This was the Ruba‘i which for several decades was used by Sufis ts as their chief vehicle of expression. Sultan Abu Sa‘id Abul-Khair, a contemporary of Sheikh Bu Ali Sina, was the first Sufi who employed the Ruba‘i to give expression to his mystic thought. He died in the eleventh century A.D. and was followed by such eminent Sufi poets as Hakim Sanai, Ohduddin Kirmani and Khwaja Fariduddin Attar.

At this time an event of very great importance took place. The Tartars shook the entire structure of the Muslim world. Many a king was dethroned and killed. Many a kingdom was devastated and ruined. The contemporary human eye saw all this ruthless annihilation and realized that all was transitory. This bloody vision gave an impetus to mystic poetry and mysticism, which have for their basic principles an unshakeable faith in the controlling forces of destiny, in the transitoriness of worldly glory, in the utter submission of the self to the will of the Almighty, and finally in the realization of self in and through the love of God. As a result of this a larger number of mystic poets flourished in this age than in any other. Maulana Room, Ohdi, Iraqi, Maghrabi and a host of other minor mystics lived in the years that followed the turbulent days of the Tartar invasion. Henceforth, mystic poetry held undisputed sway over the human heart. It purified and embellished not only the Persian language but also the various types of its poetry. The Qasida went nearly out of fashion. Maulana Room, Maghrabi, Iraqi and Sahabi never attempted it. Strictly conventional Masnawi also went out of vogue for the simple reason that in its introductory sections after the Hamd and the Na’t, it was customary to praise the king.

It is not my aim to survey the influence of mysticism on Persian poetry as a whole, nor do I mean to analyse the theory and practice of mysticism itself. My sole object is to make it clear that nearly all the Sufi poets took to the Ruba‘i, after partially discarding other types of poetry which had become associated with mundane and sometimes sordid themes.

The list of Sufi poets who lived from the eleventh to the eighteenth century is indeed along one. Most of them have written excellent ruba‘is. I am here concerned with only one of them, and what I have to say in this essay falls under two heads : firstly, the life and character of Sarmad ; secondly, his Ruba‘iyat as they have come down to us.

It is important that readers who seek information concerning the life and character of Sarmad should realize how little is known definitely about him, notwithstanding the enormous popularity which Sarmad enjoys amongst the martyrs of the early period of the reign of Aurangzeb Alamgir. Much of what has been written about Sarmad is deplorably uncritical, and I do not believe I need to offer any apology for treating the subject in a scientific spirit.

During and even after the reign of Aurangzeb, the entire bulk of Tazkira literature was produced by men whose interest did not go beyond the mere mention of a poet’s name and giving a few samples of his poetry.

Sarmad figures in almost all of these Tazkiras, but they do not in any way, improve our knowledge of Sarmad; so much so that we cannot even find his name from these sources. Mirza Mohammad Kazim in his Deh Salah, the writing of which was stopped by royal order, says nothing about Sarmad; even Mustaid Khan in his Maasir-i-Alamgiri, which was written during the reign of Shah Alam (and which incorporated Deh Salah) has not made the slightest mention of Sarmad, Probably this is due to the fact that the Mughal invasion of Bihar and Assam took place in the same year in which Sarmad was beheaded for is so-called atheism (1659 A.D.).

There are only three books which have anything at all to say about him and it is on these that we must base all our knowledge of Sarmad. The first is Mirat ul-Khayal by Sher Khan Lodhi, a contemporary of Aurangzeb who had no connection with the Royal Court. A manuscript copy of Mirat ul-Khayal which was transcribed in 1137 A. H. has been most kindly lent to me by K. B.Maulvi Zafar Hasan of the Archaeological Department. The second is Riaz ush-Shu‘ara written by Ali Quli Khan Daghistani, a noble of the Court of Mohammad Shah and a poet and critic of no mean accomplishment and integrity. Lastly there is Dabistan-i Mazahib, the authorship of which has not yet been authentically established, though the overwhelming internal evidence from the book leads one to believe that it must be the work of a contemporary author who knew important persons and places of his time rather well. To my mind it appears that these three books clear the ground and define the limits within which a solid reconstruction of Sarmad’s life can be attempted. These limits, I have to admit, are exceedingly narrow and create no occasion to speak at length and with certainty about many a point in the life of Sarmad and yet there is nothing more beyond the very meagre internal evidence which the Ruba‘iyat-i Sarmad offer to the reader. For these reasons, in the present state of our knowledge, the personality of Sarmad must be regarded as an almost inscrutable problem.

The author of Dabistan-i-Mazahib, in his discourse on the religion of Jews says that “the author had not the chances of keeping company with the wise and the learned amongst the Jews and whatever could be found in the books of non-Jewish authors about their (Jewish) faith could not be relied upon because intolerance often paints a false picture. But in the year 1057 A.H. when I reached Hyderabad Sind, I cultivated the acquaintance of Mohammad Sa‘id Sarmad who originally came of the learned of the Jews, from a sect who are known as Ribbani and who (Sarmad) after learning the principles of Jewish faith and studying Torait became a Musalman.” This quotation establishes definitely that the name of Sarmad after his conversion to Islam was Mohammad Sa‘id. What his Jewish name was, no one can tell. In most anthologies, the various compilers have prefaced the sample of the poetry of Sarmad as ‘ Sa‘ida-i Sarmad ’ which probably is due to the fact that these compilers used a portion of the name of Sarmad, i.e., Sa‘id, as the title of a selection from Sarmad’s poems,

The author of Mirat ul-Khayal says that “ Sarmad was originally from Faringistan (Europe) and was an Armenian.’ Valah Daghistani, in Riaz ush-Shu‘ara, goes a step further and adds that “his native place was Kashan.”

In the absence of any other evidence we have no reason to doubt any of these statements which are not contradictory, and can accept the fact that the emigrant ancestors of Mohammad Sa‘id Sarmad were European Jews and that they had migrated to Armenia : and that Sarmad became a Musalman, and that prior to his coming to India he lived in Kashan.

None of the Tazkaras except Dabistan-i Mazahib has anything to say about the education which Sarmad received, although there is unanimity on the point that Sarmad was really a learned man, thoroughly conversant with Arabic. Dabistan-i Mazahib says that “he studied philosophy under such learned professors of Persia as Mulla Sadra and Abul Qasim Qandraski and a host of others.” The above quotation is a positive proof of Sarmad’s learning and erudition, which adds strength to my view that a Jew who had descended from the priestly class and who had studied the sacred books of the Jews would not have changed his faith without first making a comparative study of religions, which incidentally shows that Sarmad was a really fearless person who translated his convictions into action. He certainly was born of rich parents and could afford a more expensive education than was within the reach of the average person.

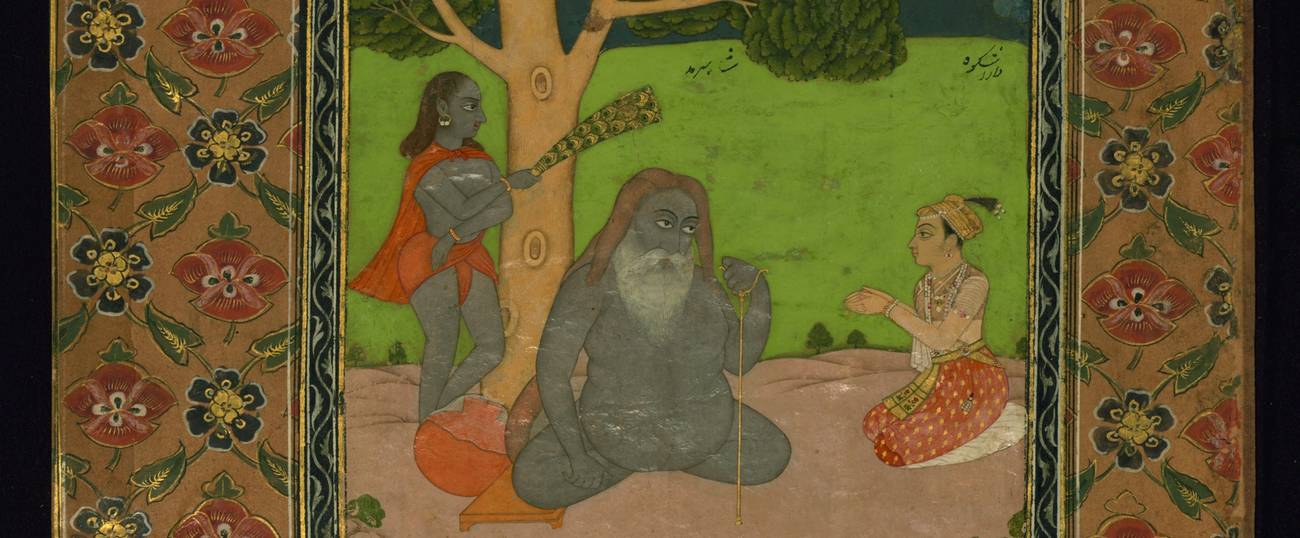

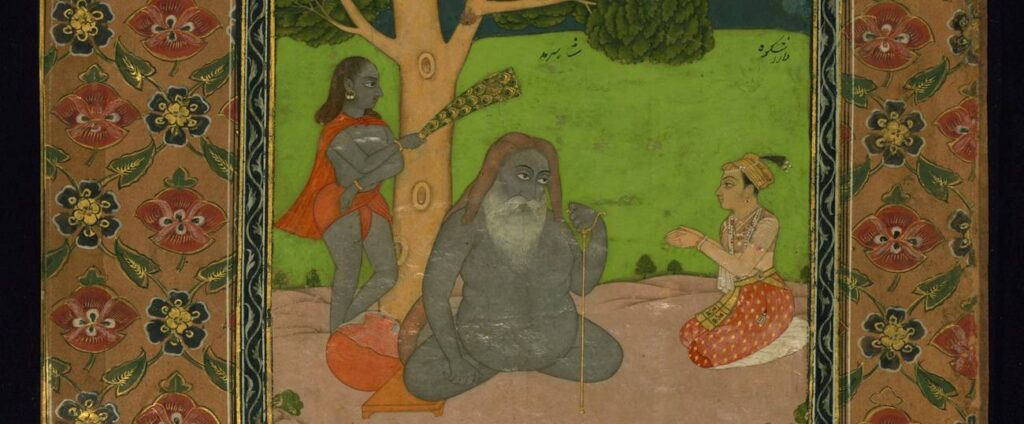

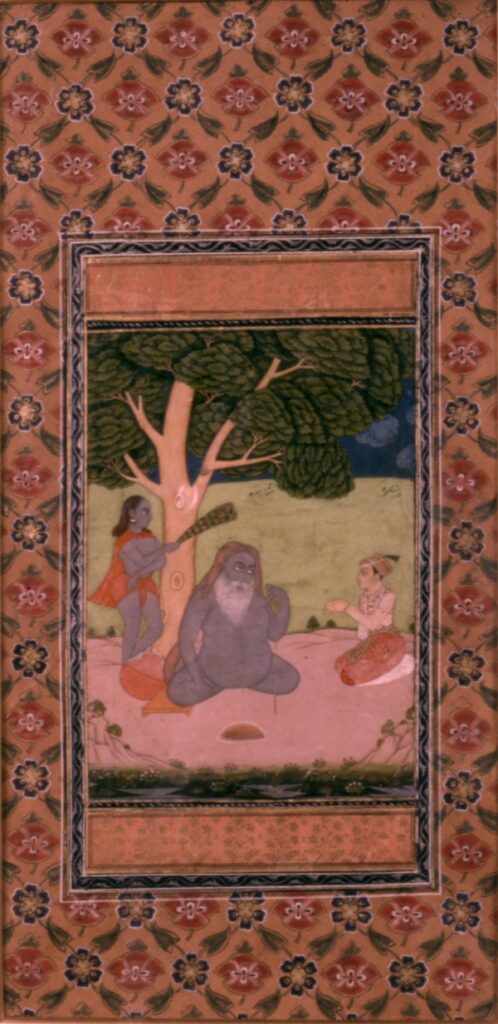

I have just said that he came of rich parents and to the reader this might possibly appear a rather audacious assumption on comparatively little data. It would indeed be so, were I not able to substantiate it from the fact that he came to India as a merchant. Dabistan-i Mazahib says that ‘eventually according to the custom of merchants he came to India by the sea-route.”_ In the palm days of the Mughal Empire most of the rich traders with valuable merchandise used to scek the Mughal Court where their wares not only fetched high prices but where the traders themselves received rich rewards for the fine taste they exhibited in the choice of those unique and priceless samples of art and craft which comprised their merchandise, And who but a wealthy merchant could afford to do this type of business. Indeed Sarmad was one of those numerous merchants, poets, painters and learned men for whom the grandeur of the Mughal Court had a great attraction. He reached India by the sea-route and landed at Thatta—a well known place in those days. And Dabistan-i Mazahib says,‘ when he (Sarmad) reached the town of Thatta, he fell in love with Abhai Chand—a Hindu boy and withdrew his hand from all things (of the world) and went nude like the Hindu ascetics.”

The fact “that the father of that Hindu boy on finding out the purity of Sarmad’s love took him into his house and the boy also got so much attached to Sarmad that he never could leave him, and studied Torait and Zaboor and other Gospels from Sarmad,’’ is an indication of that mental and spiritual phenomenon when a seemingly in-significant stimulus may bring mysterious forces into action.

This incident closed a chapter in Sarmad’s life—that of a trader—and opened up a new phase with which I shall concern myself hence forward.

It is one of the most splendid yet sinister fascinations of life that we cannot trace to their ultimate sources all the storms of influence that play upon the frail craft of an individual’s existence, Sarmad had come out to India to add to his worldly wealth, and when he did reach India, he threw away all his worldly wealth and all his worldly wisdom. As I have stated above, he took up his abode in a Hindu family, with the parents of Abhai Chand. This boy, about whom hardly anything is known, studied languages and the Scripture under Sarmad and “ translated a chapter from Torait into Persian and the author (of Dabistan-i Mazahib) after having it reviewed by Sarmad, and after having injunctions thoroughly corrected and marked, incorporated it with this chapter.” The chapter referred to in the above quotation is quite a long one and as far as I can judge, its language shows that the writer had acquired a thorough grasp of Persian. In the easy and smooth flow of his style, Arabic words and phrases are so deftly blended that they impart terseness to his sentences and grace to his diction. This Hindu boy must have cultivated a great taste for Persian because, apart from this prose specimen of his, we find also a verse of his which the author of Dabistan-i Mazahib has given in his book.

There is nothing very remarkable about the verse, but it shows the religious outlook of the Hindu boy who lived and studied under Sarmad’s affectionate guidance. It is :

“I Obey the Quran, I am a Kashish and also an ascetic; I am a Rabbi Jew, I am an infidel and I am a Musalman.”

Sarmad stayed in Thatta for quite a long time—how long, no one can say definitely. Towards the close of Shah Jahan’s reign, he had reached the Gangetic plain.

I think his wanderings took the natural course of a tourist of those days and he eventually reached the great metropolis of the Mughals about the year 1654. Dara Shikoh the heir-apparent was according to the usual custom, the governor of the metropolitan province while the other brothers governed distant provinces of Deccan and Bengal. It is a pity that our historians have not yet paid proper attention to the life and work of Dara Shikoh, who from all available testimony was a Prince of very rare gifts.

He was one of the most learned men of his age and his chief interest lay in the comparative study of religions.

When Dara Shikoh came to know of Sarmad, he lost no time in inviting him to his court. Sher Khan Lodhi in Mirat ul-Khiyalsays, “ As Sultan Dara Shikoh had a liking for the company of lunatics, he kept his (Sarmad’s) company and enjoyed his discourses for a considerable period. Eventually time took a new turn….”

It is evident that Dara Shikoh took immense interest and pleasure in the company of Sarmad who, in turn, appreciated his royal friend greatly. The circumstances which led to the imprisonment of Shah Jahan and the long and bloody struggle which ensued between his sons. do not require any comment from me. I have only to mention that this ended in the capture, imprisonment and finally the death of Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb’s accession to the throne. Mirat ul-Khayal says that, with the accession of Aurangzeb, the new and foolish creeds of Akbar and Jahangir were rooted out, the customs of Murad Bakhsh and Dara Shikoh were set aside and religion once again had the sway which it deserved. In the new regime, Sarmad whose life was not led in accordance with the Shariat was not to be tolerated any more. He had many a crime in his charge-sheet for which sooner or later he had to stand a trial.

There is a diversity of opinion about the causes which led to the execution of Sarmad. It is said in Tazkirat ul-Khayal that the Moulvis took offence at a certain quatrain of Sarmad which to them appeared to deny the bodily accession of the Prophet Mohammad (peace be on his soul)) to the heavens. “Whoever came to know the real secrets of existence, he traversed long distances easily; the Mulla says that Ahmad ascended the heavens and Sarmad says that the heavens descended to Ahmad.”

It is also said that Aurangzeb, who knew all about the close friendship of Sarmad and Dara Shikoh, did not like any one of Dara Shikoh’s admirers to survive. He got rid of most of them on political pretexts ; but for Sarmad, the subterfuge of religious disbelief was needed. It was not very hard to find one, and so Mulla Qavi, the Qazi-ul-Quzzat, was sent to Sarmad, to ask him the reason of his nudity. Sarmad in reply recited the following Ruba‘i incidentally hurting Mulla Qavi’s feclings by an insulting pun on his name.

“ The One of lovely stature has made me so low and His eyes by giving me two wine-cups have taken me out of my senses ; He is by my side and I am in search of Him. This novel thief has stripped me of everything.”

Mullah Qavi took the story to Aurangzeb who had Sarmad summoned before a religious court where he was to be tried for his various religious crimes. Valah-i Daghistani writes on the authority of Khalifa Ibrahim Badakhshani who lived his pious life towards the end of the reign of Aurangzeb, that when Sarmad refused the order of the court to put on clothes, Aurangzeb argued that no one could be hanged with any justification for going undressed, At last Sarmad was asked to recite Kalima-i-Taiyaba. He, according to his habit, recited only La ilaha—there is no god—and did not go any further. When he was questioned about his heretic utterance, he said that in his life he had so far met only with the negation of life and love, and as he did not actually know the positive side of it, he would not speak of it. Now the charge of heterodoxy was completely established and Sarmad stood condemned, firstly, for being a partisan of Dara Shikoh, secondly, as one who did not believe in the bodily accession of the Prophet to the heavens (Miraj-i-Jismani) ; and thirdly, as one who went about nude and denied the existence of God because he had not had any personal knowledge of Him. Judgment was delivered and Sarmad was sentenced to be executed. When Sarmad was taken to the place of execution and the executioner wanted to bandage his eyes according to the custom, he asked him not to do so and looking at the executioner smiled and said:

“ Come in whatever garb you may, I recognise you well.” So saying, he bravely placed his head under the sword and gave his life.

Some people believe that the place where Sarmad lies buried is not the spot where he was beheaded, but Valah Daghistani is definite on this point. He says, “ At a side of Masjid Jamay they beheaded him and buried him at the same place. The writer of these words has twice had the honour of visiting his sacred tomb and in all the four seasons there is plenty of verdure on his grave. In reality it is a source of great peace to be able to visit this sacred shrine.”

There are only two tombs on the sides of the Jami‘ Masjid ; one is on the north which is in a very uncared-for condition and is said to be the grave of an unknown saint while the other which lies on the eastern side to the right is rather well kept, and the popular belief is that this is the tomb of Sarmad. It is generally known as the grave of Haray Bharay, and is held in great reverence by the citizens of Delhi. Valah Daghistani mentions on the authority of Khalifa Ibrahim Badakhshani that although Sarmad never recited the whole of Kalima-i Taiyaba in his life time, yet after his execution, people heard his chopped head reciting the whole of the Kalima. It is strange that this story is current in Delhi even now when about three centuries have passed, and I do not doubt that it had its origin in the popular belief of Sarmad’s contemporaries and the successive generations that Sarmad was a great saint to whom the shackles of convention and the rituals of religion were irksome, and that he had the courage of his convictions when he broke those fetters and paid the penalty by giving his life. Nothing is known of Abhai Chand’s fate. It cannot even be said whether he was with Sarmad at the time of the execution.

No complete collection of Sarmad’s poetical works is available, and it is commonly believed that his poetic effusions are confined to Ruba‘iyat only. I should have hesitated to challenge this belief, were it not for the fact that external evidence (from the three books on which I have mainly based this essay) as well as internal evidence from the quatrains of Sarmad is conclusive on this point. The author of Dabistan-i-Muzahib says, “ Sarmad is the creator of good verses” and quotes a Fragment which Sarmad composed in praise of Shaikh Mohammad Khan, the Peshwa of Dara-i-Namdar Sultan Abdullah Qutab Shah. Sher Khan Lodhi in his Miérat ul-Khiyal has quoted a ghazal which has four verses; the last verse containing the nom-de-plume of the poet. Valah Daghistani in his Riaz ush-Shu’ara also confirms this belief by attributing to Sarmad a variety of Persian verses. Sarmad himself in a quatrain says, I am not interested in the thought and actions of any one; but in Ghazal I follow the trend of Hafiz. Indeed in Ruba‘i, l am a disciple of Khayyam but I do not sip long at his wine-cup either.” This testimony leaves no room for mere guess-work and makes it at once clear that Sarmad tried his hand at more than one type of Persian poetry. He wrote Fragments, Ghazals and Quuatrains, but the last indeed held a sway over his imagination. In various collections the number of his quatrains varies from three hundred and ten to three hundred and twenty-one. In these collections, it is not at all unusual to come across one or two quatrains the authorship of which has now definitely been attributed to Khayyam. Sahabi Astrabadi or lesser luminaries. The reason for this overlapping is simple. The uncritical compiler has often taken a certain quatrain to have been written by one poet or another only on the basis of a similarity of theme. I have no criterion by which to judge and finally attribute the authorship of any one of these disputed quatrains to Sarmad. I have taken great care to include only those quatrains which appear in all the collections and which, as far as my meagre knowledge of Persian poets goes, have not been attributed to anyone else. I cannot hazard a guess as to the agency which preserved Sarmad’s quatrains. Hs quatrains, most of them anyhow belong to that period of his life when his interest did not he in worldly things. He lived in a state of perpetual ecstacy when the method of expression appears to be that of generating the thought in all its awful intensity and scope, and not caring for it after its creation.

He could not strike an invariable balance wherein the individual subdues ecstasy; instead the sea of ecstasy kept on dancing and raging so much that even when he was face to face with the grim fact of the universe, that is, death; he smilingly courted it and said :

He burnt me without any reason, look at the fun,

He killed me without any reason, look at my Maseiha

O you who are ignorant of the charms of Yusuf’s face,

Look at the pangs (of love) which Ya‘qub and Zuleikha bore.

O you who are astonished at my ugly face.

For a brief minute look at that lovely face.

You have seen king, darwish and qalandar,

Look at Sarmad, ecstatic and ill-famed.

Indeed, ecstasy is one of the chief features of Sarmad’s quatrains. His quest after eternal beauty does not leave any delight for him in worldly things. His own self is lost to him. The world, which he forsook so dramatically, had no charms for him. Religion with its hopes and fears and future promises does not attract him and, although he knows that mankind has but a few pursuits in life, yet he does not want the glitter and glamour of these, because his ‘ hot desire’ is leading him to the search of the ‘Great Self.’ He says:

Some love the world; some to the church take flight,

Yet not in either may I find delight.

Only the knowledge of Thy Self can sate

My hot desire, Ah ! tear the veil outright.

But no one can say that Sarmad made his choice without any deliberation. He weighed the pros and cons, he estimated the gain and the loss and stood undecided for a long time:

Sarmad. why wrestle in a long debate.

There are two ways to choose: make one thy fate:

Either to take Him ever to thy heart

Or else to leave Him and be desolate.

Finally he came to know the secret of man’s happiness and realized that eternal happiness is not given to everyone, nor is it given without the ungrudging payment which one has to make in the shape of undergoing great misery and hardship and annihilation of one’s self.

If fly knows nothing of the moth’s desire

Nor are love’s tears pearls strewn among the mire.

Love waits eternally and blooms in pain

The selfish know not sorrow’s sacred fire

At last the die is cast and he sacrifices all that he possesses. He has undergone all the misery and hardship that was possible, at the hands of the men of this world and even then is prepared to face everything which may fall to his lot, not with the resignation of the pious but with the joy of a lover’s heart. The state of perpetual ecstasy has come and he proclaims it in the following words :

Now am I come into one high estate.

A lover, and [envy not the great,

Love only binds me, I can stand atone

And hurl a challenge at malignant fate.

Love only holds me and my heart is light

Phant as wax, and like the candle bright

And by the tight of love that shines from me,

I know the secret of men’s hearts’ delight.

It is evident that one who has arrived at this stage, must necessarily have a supreme contempt for those whose entire life is devoted to hypocrisy and those who outwardly claim to seek Him, but inwardly keep on seeking worldly goods, In Surmad’s contempt for such persons we do not find hatred but sympathy. He wants to reclaim the strayed and the lost by merely porting the right path to them. He warns then: of the pitfalls which beset their path and gives this affectionate warning:

The woollen mantle, the Zunnar beneath

Are for hypocrisy and lies a sheath.

Ah, don them not, or sorrow, tears and shame

Shall be a burden to thee until death.

To Sarmad, greed appears to be the chief source of human misery because once one starts to pile up worldly goods, one wants to go adding on to this growing pyramid until death comes when the whole hoard becomes more useless than the dust in which one is buried. Sarmad puts it in the following words:—

Greed’s slaves are prisoners, although their lot

Comprise a kingdom: or an acre plot.

The thread of life hath all too brief a span,

Let not greed twist it to a tangled knot.

But Sarmad in his denunciation of greed does not advocate the total withdrawal of man from acquiring wealth, which after all is a neeessity. He only wants that our pursuit of wealth should not blind us to other aspects of life and other values. Sarmad pleads for moderation and I do not doubt that he can well claim our consideration even today, He says:

The clever man whose heart’s on riches set,

Is like a bird snared in the fowler’s net.

In moderation ever lies content

Great wealth but makes the burdened spirits fret.

Along with this warning, Sarmad warns us to beware of the loss of balance which comes in old age. It is clear that in youth when everything is on the ascent and the sap of life flows vigorously and quietly, we do not clutch at all the petty chances which are offered to us. But when we are old, and when our powers begin to wane, leaving us “sans eyes and sans teeth,’ we want to make the best of every little trifle. The balance of our life is gone and the ‘equation’ is lost. Lust for the possession of all that glitters, be it gold, be it physical beauty, be it the tending of ego, grows day by day, Sarmad knows this secret and denounces it, Our denunciation of our own selves is often lukewarm and lacks sting. Consequently, Sarmad does not denounce himself but his ‘mad heart.’ He says :

My mad heart ne’er was reconciled to fate,

Plotting and scheming ever, soon and late:

And though the flower of my youth has fled

Still is my young desire unsatiate.

What utterance could be more pathetic and more true !

In youth, the streak of old age in us is the wisdom of the old and in old age the remnants of youth in us are the memories of our young days. The former is often denied to some of us but the latter is always portioned out to us as our only consolation. Sarmad has repeatedly and most beautifully sung of his delicious memories and the following is a good example of it.

Once with my friends in gardens bright with flowers,

In sweet companionship I spent life’s hours,

Now only memory is left to me

And skies loom dark on those once radiant bowers.

But even when Sarmad is weeping his heart out on the memories of days gone by, he realizes the one supreme fact of all existence —death. Death has taken away many, and it will take away many more—therefore we should always be prepared for it. This will take away the ghastliness of death and will prepare us, after having lived our lives well, to welcome it as Sarmad did.

Lo! All the loved ones to the dust must yield,

For Death’s the huntsman and the world’s his field.

Low in the dust each one of us must lie,

Though he should have the heavens for his shield.

And

Though all the universe should know thy fame,

Though sun and moon were minted with thy name,

Though Ceasar and Faghfoor were thy slaves,

It would avail thee not when Azrael came.

Sarmad’s quatrains are full of wise thoughts and natural philosophy, but the note of love of the ‘Eternal Beauty’ is predominant and runs through everything as the refrain of his music, This note has all the charm of Sufi belief. It rakes Sarmad see the ‘Beloved’ in all that exists in the universe. The cause and the effect of existence are blended together and only go to show that what exists is of Him and from Him. Sarmad says:—

Which is the idol, which the fashioner?

Which is the lover and the loved one here?

Ask in the church, the temple, the Ka‘ba,

And all is silence, all is darkness there.

Yet in the garden where the sunshine glows

One Perfect Presence moves in all that grows.

He is the lover, He is the beloved,

He is the bramble and He is the rose.

And because He is present in all creation, therefore, to try to find Him in any one particular place is futile.

Not only underneath the temple’s dome,

But in the universe He makes His home.

Fools gather, noisily to talk of Him.

The wise of heart, to Him alone will come.

All the same it is not difficult to find him out, because;

Is the heart wise? then the Beloved is there,

Does the eye see? it sees Him everywhere.

Does the ear hear? it hears but talk of Him.

Does the tongue speak? it lays the secret bare.

But to become truly a part of Him requires great effort;it requires self-annihilation.

Only when being has been left behind

Canst thou the only source of being find.

The cowards perish—only the burning soul

Can see the flame and not be stricken blind.

I do not propose to go any further and be in the way of my readers’ first-hand appreciation of Sarmad’s quatrains. I have ventured to give them the translation in English of some of them. No-one can be more conscious of the imperfections of these translations but I present Them in the hope that some abler pen will be moved to render them to that perfect form of poetry which Sarmad’s quatrains richly deserve.

Poetry

O Manifest yet hidden, come to me.

Far have I wandered in the search for Thee.

Close have I longed to clasp Thee to my heart

Yet still Thy face behind the veil I see.

Some love the world, some to the church take flight,

Yet not in either may I find delight.

Only the knowledge of Thy Self can sate

My hot desire; ah, tear the veil outright.

O Wooer of man’s heart. beloved Friend,

Thy ways are my ways, unto Thee I bend;

Thou dost not show Thyself, yet everywhere

Thou goest with me unto journey’s end.

I sought His savour in the morning breeze,

Sought Him in flowers underneath the trees,

Yet in the quiet places of the heart

I found His presence sooner than in these.

We know His presence when our hearts are moved;

He is the lover, aye, arid the beloved.

Open your eyes with joy, O man, and see

The hundred ways in which His love is proved.

Now He seems kind, now fickle as the dew.

Each moment gleaming with a different hue.

Open thy arms to Him, see with clear eyes

And thou shalt know Him ever to be true.

Is the heart wise, then the Beloved is there;

Does the eye see, it sees Him everywhere;

Does the ear hear, it hears but talk of Him;

Does the tongue speak, it lays the secret bare.

Not only underneath the temple’s dome

But in the universe He makes His home.

Fools gather noisily to talk of Him.

The wise of heart to Him alone will come.

So, I rejoice that I have known His grace

The bounteous breath, the glory of His face.

I made no loss, profit alone was mine

In this transaction, in love’s market place.

Lo! in the secret cup the wine is red,

Yet none may taste of it whose soul is dead.

By God, O Pharisee, you know not God

For whilst you mumble prayers, the secret’s fled.

Which is the idol, which the fashioner ?

Which is the lover and the loved one here ?

Ask in the mosque, the temple, the Ka’ba

And all is silence, all is darkness there.

Yet in the garden where the sunshine glows

One perfect Presence moves in all that grows.

He is the lover, He is the beloved,

He is the bramble and He is the rose.

Behold, within ourselves we two are one,

I know not how this miracle is done.

He is the ocean, I the eup—ah, no!

How should that make the perfect union?

My wayward heart with love is lifted up

On colour and on scent of flowers I sup.

If with His love’s clear nectar I am filled

Shall not the wine spill from the brimming cup?

I have surrendered Being and have not thought

What Being is: my spark of smoke knows naught,

I have surrendered heart and life and faith

And found a profit that I had not sought.

Sarmad, why needst thou seek Him endlessly?

If He be loved, then He will come to thee.

He knows the best, sit then in quietude

Till thy heart whisper softly—“It is He.”

If fly knows nothing of the moth’s desire,

Nor are love’s tears pearls strewn among the mire.

Love waits eternally and blooms in pain,

The selfish know not sorrow’s sacred fire.

I asked the wilderness of wisdom’s leaves,

What, then, is Being? The mirage that deceives

Mocked at my quest: I do not even know

Who made the pattern that the spider weaves.

Love pours strange vintage in unstinted measure:

Sorrow and yearning fill the cup of pleasure.

Yet to the tavern of the world there come

Love’s victims, craving still this bitter treasure.

Seek the Beloved, who will ne‘er depart

From thee, nor cause thee bleeding of the heart.

Seek the Beloved, in thine arms to rest

In union that none can tear apart.

Now am I come into one high estate,

A lover and I envy not the great,

Love only binds me, I can stand alone

And hurl a challenge at malignant fate.

Love only holds me and my heart is light,

Pliant as wax and like the candle bright,

And by the light of love that shines from me

I know the secret of men’s hearts’ delight.

Sarmad, why wrestle in a long debate?

There are two ways to choose; make one thy fate :

Either to take Him ever to thy heart

Or else to leave Him and be desolate.

Only when Being has been left behind

Canst thou the only source of Being find.

The cowards perish—only the burning soul

Can see the flame and not be stricken blind.

Thou canst not ever find the friend of friends

Whilst yet thy mind to trivial things attends:

Thoughts of aught else but Him can only raise

A barrier that no desire transcends.

Go to the tavern, not alone, but seek

The cup-bearer of the rose-petalled cheek;

Drink not forgetfully or carelessly;

The wine of life is poured not for the weak.

I am so wise, madness has come to me,

Who can describe Love’s utter ecstasy.

Can the wide sea be measured in a cup?

O dream of madness, O absurdity!

Now in the desert, now in the garden-close,

Now in the dale, now where the hill-wind blows,

Now by the way of spirit, now of flesh :

All these are paths to truth’s One Perfect Rose.

I gaze unknown on the Beloved’s face,

In secret I adore His perfect grace,

The world is busied with its own pursuits

But my quest leads me to a different place.

Through all eternity the bubbles rise.

Dances the mirage ever in the skies,

Ever the old harp waits for a new song.

And this old house empty for ever lies.

My heart must ever seek Love’s pain and fret,

I take its burden up without regret.

Waste not your breath advising me, O Priest,

My feet on different paths to yours are set.

How may one find Him out by argument?

Reason and evidence in vain are bent.

Wearing out heart, wearing out brain and eye,

Within the fold of blinding reason pent.

Though Thou art hidden, yet behind the eye

Thou wellest, knowing well my secret. Aye,

And like the lamp behind its coloured shade

Thou sheddest light for me to travel by.

How many of earth’s forms Thou makest Thine,

Garden and desert, cypress, jessamine,

Sometimes the scent of flowers, sometimes a light

That Thou alone now upon all dost shine.

Once with my friends in gardens bright with flowers,

In sweet companionship I spent life’s hours,

Now only memory is left to me

And skies loom dark on those once radiant bowers.

Death is the destiny of worldly things,

Desire for worldly riches only brings

Hardship and disappointment in its train;

Wealth is a tyrant mightier than kings.

Lo ! how a dinar-greedy eye doth blind !

How fervently each to each is unkind !

Fear not so much the snake or scorpion

As that incarnate sting, a greedy mind.

How futile is the thirst for wealth and power;

Futile the plots and schemes that o’er us tower;

Since in this flesh we have so brief a home

Why seek for wealth which lasts but for an hour?

Ever desire and discontent I see;

Men seek the world for wealth eternally.

This ancient house is full of sufferers

Yet few can find their golden remedy.

The clever man whose heart’s on riches set

Is like a bird snared in the fowler’s net,

In moderation ever lies content ;

Great wealth but makes the burdened spirit fret.

Greed’s slaves are prisoners, although their lot

Comprise a kingdom or an acre plot.

The thread of life hath all too brief a span,

Let not greed twist it to a tangled knot.

The woollen mantle, the Zunnar beneath,

Are for hypocrisy and lies a sheath.

Ah, don them not, or sorrow, tears and shame

Shall be a burden to thee until death.

Who from the godly hypocrites can tell ?

A pious action yet may lead to hell.

Zahid, you say, “Drink not, but be like me.”

Tell that to those who know you not so well.

Lift not thy head so high, O Zahid, lest

Thou shouldst be humbled and must beat thy breast.

“ Camphor” they name the negro slave, but thee

They name “The Pious” in derisive jest.

Padshah am I, no beggar, crawling, sly.

Greatly I love, and from one danger fly.

And, Zahid, though I worship in the mosque,

If thou art Musalman, so am not I.

No robe of base hypocrisy I own,

I bend the knee before one King alone.

Desiring nothing, all the world is mine,

The tavern bench is better than a throne.

This body perishes, However fair;

The straw flames high, but soon is lost in air.

Death spreads his net, and frail humanity

Is driven pitilessly to its snare.

I have been up and down over the earth

In times of plenty and in times of dearth,

Seen towns and citics, deserts, hills and plains

And found in all of them but little worth.

My mad heart ne’er was reconciled to fate,

Plotting and scheming ever, soon and late,

And though the flower of my youth has fled

Still is my young desire in-satiate.

Who has seen how life moves on quiet wings

Through endless autumns into endless springs

Knows that the form and colour of this world

Are but the shadow of eternal things.

Though all the universe should know thy fame,

Though sun and moon were minted with thy name,

Though Ceasar and Faghfoor were thy slaves,

It would avail thee naught when Azrael came.

Lo ! all the loved ones to the dust must yield,

For Death’s the huntsman and the world’s his field.

Low in the dust each one of us must he,

Though he should have the heavens for his shield

Seek not the world, it is thine enemy,

Bringing heart-burning, shame and grief to thee.

Only by thought may the true path be found,

Then let thy sense be balanced evenly.

O Greed, why dost thou wish to serve a crown?

Soon from the court to death thou must go down,

Kings have their brows knit and are hard to please

And all the world not worth one royal frown.

How foolish is the quest for worldly fame,

For only like the seal one makes the name.

That first is carven with the painful tool

And then is blackened with the ink of shame.

– IMAGE COURTESY THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM

Note – This article was published in Islamic Culture journal in 1933 . For our readers we are re publishing it with some edits

Read Rubaiyat of Sarmad on Sufinama –

https://sufinama.org/poets/sarmad-shaheed

Guest Authors

- Aatif Kazmi

- Absar Balkhi

- Afzal Muhammad Farooqui Safvi

- Ahmad Raza Ashrafi

- Ahmer Raza

- Akhlaque Ahan

- Arun Prakash Ray

- Balram Shukla

- Dr. Kabeeruddin Khan Warsi

- Dr. Shamim Munemi

- Faiz Ali Shah

- Farhat Ehsas

- Iltefat Amjadi

- Jabir Khan Warsi

- Junaid Ahmad Noor

- Kaleem Athar

- Khursheed Alam

- Mazhar Farid

- Meher Murshed

- Mustaquim Pervez

- Qurban Ali

- Raiyan Abulolai

- Rekha Pande

- Saabir Raza Rahbar Misbahi

- Shamim Tariq

- Sharid Ansari

- Shashi Tandon

- Sufinama Archive

- Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

- Syed Moin Alvi

- Syed Rizwanullah Wahidi

- Syed Shah Tariq Enayatullah Firdausi

- Umair Husami

- Yusuf Shahab

- Zafarullah Ansari

- Zunnoorain Alavi